DESCRIPTION

Introduction to the phonetics of English vowels.

PURPOSE

To understand how vowel phonemes are produced in English. By means of studying different vowel phonemes, you will be better equipped to reproduce them more clearly and become a more articulate English speaker. What’s more, you will be able to identify different vowel sounds and avoid misunderstandings in the future.

PREPARATION

Before beginning this unit, just make sure you have the IPA (International Phonemic Alphabet) chart at hand so that you can easily identify the phonemes being discussed. You may also want to keep a good dictionary at hand.

GOALS

Section 1

To identify different vowel phonemes: short and long vowels

Section 2

To distinguish monophthongs from diphthongs

Section 3

To recognize the schwa sound

Section 4

To describe concepts linked to the combination of vowels and consonants (tonicity, intonation, homonymy, homography and polysemy)

INTRODUCTION

In the following sections you will learn how to identify and classify vowels according to different tongue heights, duration and articulatory positions. You will learn that tongue movement and height play great roles in vowel production. What’s more, you will study how to identify different diphthongs and also classify them. Furthermore, you will learn how stress and intonation can interfere with the message being conveyed. Finally, you will study examples that show why in English graphemes and phonemes do not allow for a one-to-one correspondence.

By the end of this unit you will be able to classify, identify and correctly reproduce vowel phonemes.

SECTION 1

To identify different vowel phonemes: short and long vowels

Twenty vowel sounds

Before we get started just take some time to think about the following question:

How many vowels are there in English?

Check the answer in next paragraphs.

Check the answer in next paragraphs.

Check the answer in next paragraphs.

Most people will probably answer that the English language is composed of five different vowels. Who hasn’t heard of a, e, i, o, u? More astute English learners will probably add another one to the list: y, and will claim that there are six vowels in English.

This, however, just goes to exemplify a common mistake most learners make: to mistake sounds for spelling, by assuming that there is a one-to-one correspondence between spellings and phonemes.

English, however, abounds with examples that defy such assumption.

The same spelling may be reproduced by different sounds, meaning that there may be two or three sounds associated with the same spelling.

Let’s think of the letter a, for example.

In the word about the first phoneme is actually called schwa, which is one the most common phonemes in English, and is represented as /ə/.

In the word calm, the phoneme represented by the letter a is, in fact, another one, the phoneme

Long and short vowels, stressed and unstressed phonemes, monophthongs and diphthongs may be spelled as the letter a.

This is definitely confusing! – you may be thinking.

Well, not really.

It is only confusing when we assume that phonemes and graphemes are one and the same. So, in the following sections we will be clearing up any confusion regarding vowel production. You will be surprised to know that seven different phonemes are represented as the letter a, as we can see in the words below:

Jack, yacht, about, football, cable, share, private

Besides, you will probably be surprised to learn that English has, in fact, twenty vowel sounds. So, without further ado, let’s get started!

Vowel description

Vowels play a central role in the English language. They are syllabic phonemes, that is, they are able to form syllables on their own.

Friendly reminder

Remember that while certain words may consist of vowels alone, the same cannot be said about consonants.

There are other differences, though, that refer to how these phonemes are described.

Other factors come into play in vowel description.

To produce front vowels the front of the tongue is the highest point.

The back of the tongue, on the other hand, is higher when we produce back vowels.

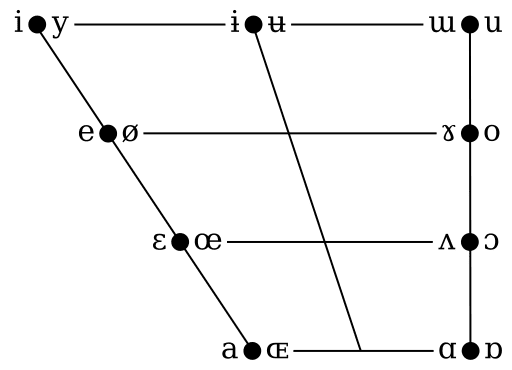

British phonetician Daniel Jones (COLLINS & MEES, 2013) devised a system that describes where the tongue is positioned during vowel production regardless of language and accent. This reference system, since it is theoretical, describes the vowel possibilities in any language.

There are eight cardinal vowels, or reference vowels, that together form a trapezium which is aimed at describing the vowel possibilities in any language.

Front vowels are on the left, whereas back vowels are on the right. In the upper area, two vowels are placed at opposite ends: the phonemes /i/ and /u/. These are extreme vowel sounds, and other phonemes are described in reference to them. /i/ and /u/, then, establish the upper vowel limit.

In the lower area, two more vowels - /a/ and /ɑ/, also represent extreme possibilities for open vowels (remember that the tongue is at its lowest, allowing for an open mouth cavity). They establish thus a lower vowel limit.

By analyzing the trapezium, then, we come to the following classification for cardinal vowels: /i/: front close, /u/: back close, /e/: front close-mid, /o/: back close-mid /ɛ/: front open-mid /ʌ/: back open-mid /a/: front open /ɑ/: back open.

Tongue shape, however, is not the only relevant factor here. Vowels are also described in terms of:

Lip shape

Position of the soft palate

Duration

Tongue and lip shape

rounded or unrounded

nasal or non-nasal

long and short vowels

held constant or undergo change

Lip shape

rounded or unrounded

Position of the soft palate

nasal or non-nasal

Duration

long and short vowels

Tongue and lip shape

held constant or undergo change

Duration

Duration here, as a phonetically relevant category, is not taken as an absolute measure, but, as a relative length of sounds. The duration of a phoneme is thus considered in relation to the duration of another one. The phoneme /i/ in ship is relatively shorter than /i˸/ in sheep, and this single difference – duration – is responsible for identifying two different nouns. /i/ is a short vowel, whereas /i˸/ is a long one. There are, though, more vowels that can be categorized by means of duration.

Let’s see more examples!

Short vowels

Try saying these words:

sit, bet, mat, shut, plot, foot, about

Now, try to answer the following question:

What do these words have in common?

If you answered that they are composed of long vowels, sorry, the answer is incorrect. Try again!

If you answered that they are composed of short vowels, then, you are right!

These words exemplify the seven different short monophthongs we have in English, namely /i/, /e/, /æ/, /ʌ/, /ɒ/, /ʊ/ and /ə/.

Friendly reminder

/i/, as in sit;

/e/, as in bet;

/æ/, as in mat;

/ʌ/, as in shut;

/ɒ/, as in plot;

/ʊ/, as in foot;

/ə/, as in about.

Short and long vowels

Do you know the difference between short and long vowels? Let’s find out!

/i/

To produce this phoneme, you should keep your lips relaxed and slightly parted. Also, you should keep your tongue high. Just remember that this is a short, quick sound. If you prolong the sound and keep your lips tense, as in a smile, another phoneme will be produced. This vowel is found at the beginning and middle of words and is spelled as y, i or ui.

Example:

sin, symbol, quick

/e/

Your tongue should also be high to produce this phoneme, near the roof of the mouth. You should keep your lips slightly spread and unrounded. Let’s compare two words that may seem similar sounding, but that are actually composed of different phonemes: pen and pain. In the first one, the short vowel /e/ is used, in the second one, nonetheless, the phoneme /ei/ is used. To pronounce /e/ you should open your mouth wider than for /ei/, but not as wide as to produce pan. /e/ is found at the beginning and middle of words and may be spelled as e or ea.

Example:

and, egg, any, dead, meant, head

Some of the less frequent spellings for the phoneme /e/ are a, ai, ie, ue and eo.

This is what happens in the following words:

any, again, friend, guest, leopard

The letters ea before d are also usually pronounced as /e/.

Example:

ready, dead, ahead

/æ/

This is the phoneme in the word pan, mentioned before. Differently from the previous phonemes, you should keep your tongue low to produce this sound. Your jaw is also wider, especially when compared with the previous phoneme /e/. You should keep your lips spread as well. If your mouth is not wide enough, you may say bed instead of bad, and bet instead of bat. Just remember to spread your lips and open your mouth. The phoneme does not occur at the end of words and is usually spelled as a, in words such as:

apple, cat, back, angry

The combination of letter au is a less frequent spelling for the phoneme in question, such as what happens in the following words:

laugh and laughter

/ʌ/

Your lips, jaw and tongue should be relaxed to produce this sound. While the lips are partly parted, the jaw is slightly lowered. The tongue is also in a mid-position in the mouth. The phoneme /ʌ/ does not occur at the end of words and is usually spelled as u, for instance, in words such as:

us, ugly, much, uncle

It may also be spelled as o, in words such as:

love, done, mother

Less frequent spellings are oo, oe, ou and a.

Examples:

cousin, trouble, flood, what, does

Attention

/ʌ/ only occurs in stressed syllables.

/ɒ/

This vowel is at the lower end of the trapezium, which means that your tongue is kept low to produce this sound. In fact, the tongue is flat, on the floor of the mouth. Your jaw is also kept low. Your lips should be kept apart, as if you were yawning. The letter o in English is usually pronounced as /ɒ/ in words such as:

top, positive, not

This vowel sound does not occur at the end of words and is usually spelled as a or o. When the letter o is followed by b, d, g, p, t and ck, it is pronounced as /ɒ/.

Example:

robin, rod, stop, pocket

The letter a, when it precedes the letter r, is also pronounced the same way.

Example:

farm, cart, start

/ʊ/

This is another short, quick sound. Therefore, your lips should barely move while you produce it. You should keep your lips partly relaxed and parted. You tongue is kept also high to produce this sound and your jaw is kept slightly low. This phoneme only occurs in the middle of words and is usually spelled as u, oo or ou.

Let’s check some examples:

book, cook, foot, could, should, cushion

Sometimes the letter o is also pronounced as /ʊ/, as in the following words:

wolf, woman

Comments

/ə/- We will be discussing this phoneme later, in another section.

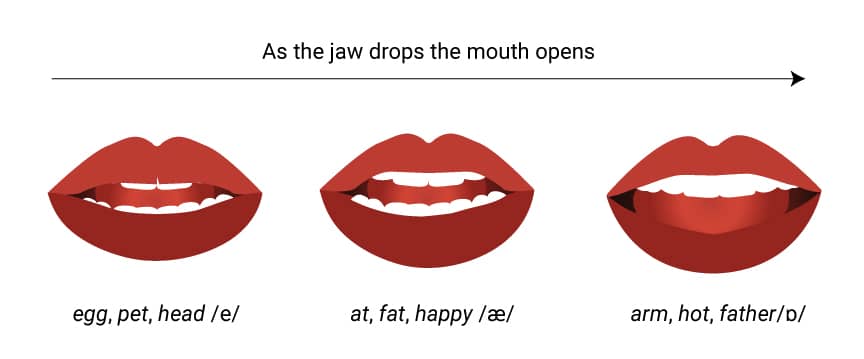

It may be a bit hard to differentiate some of these short vowels. /e/, /ɒ/ and /æ/ may cause some confusion, as they seem at first too similar. One thing to be attentive is to the position of the jaw and, consequently, to how open the mouth is. While the jaw is completely dropped to produce /ɒ/ (the mouth is then wide open), it is not as low to produce /e/. It goes as follows: /e/ ≶ /æ/ ≶ /ɒ/.

Long vowels

Now pay attention to the words below:

feel, calm, board, moon, herd

What do you notice? Differently from the words discussed in the previous section, these words contain longer vowels. Comparatively, then, these monophthongs are longer. There are five long monophthongs in English: /i˸/, /ɑ˸/, /ɔ˸/, /u˸/ and /ɜ˸/.

/i˸/

To produce this phoneme your tongue should be high and your jaw should be almost completely raised. You should also feel the tension in your lips, as they are kept in a “smile” position. Just make sure you prolong the sound, otherwise eat will sound like it. This phoneme is found in the beginning, middle and end of words. E, ee, ea, and ie may be pronounced as /i˸/, as exemplified by the words:

mean, eager, eel, be, niece

Less frequently the letters i and eo may also be pronounced as /i˸/:

people, police

/ɑ˸/

This is a very common sound in a doctor’s office. There is a clear reason for that. To produce this sound your tongue position is really low (this vowel is at the lower end of the trapezium), which means that your mouth is kept wide open. What’s more, this is a long vowel, so it should be prolonged.

Now let’s compare some words! The words had and hard, at first, may sound pretty similar. But while the former is composed of a short vowel /æ/, the latter has a long vowel in it /ɑ˸/. The following words also exemplify the same phenomenon:

fat and fart; hat and heart; cat and cart; match and March

Friendly reminder

Just remember that in the words fart, heart, cart and March the vowel’s length is longer.

/ɔ˸/

Before we delve into the details of this vowel sound, just take some time to think about the following pair: bot and bought. Can you notice any difference? Are the vowel sounds the same or different? And how do they differ?

Can you notice any difference? Are the vowel sounds the same or different? And how do they differ? Once again we are dealing with a short/long vowel comparison. In the first word the short vowel /ɒ/ is being used, whereas in the second one, the long vowel /ɔ˸/ is used instead. There is another difference, apart from the duration, though: the shape of the mouth. To pronounce bought your mouth is slightly tighter and more rounded. The following pairs also show this difference:

cot and caught; bod and bored; what and wart; shot and short; spot and sport

/u˸/

Your tongue should be high to produce this sound. Your lips should be tense and in a whistling position. Differently from what happens in the production of /ʊ/, this is a long sound. If we compare pull and pool, you will realize that to say the latter you have to protrude your lips and make sure that you prolong the pronunciation of the vowel. Except for the word ooze, this phoneme does not occur in the beginning of words. /u˸/ may be spelled as u, oo, o, ew and ue.

Examples:

rule, cool, do, new, blue

/ɜ˸/

Your tongue is slightly low when you produce this sound, placed in the middle of your mouth. This long vowel is also produced with your lips relaxed. It is normally spelled as -er, as in words such as:

person, her

Sum up

To sum up, while manner and places of articulation are unimportant factors in vowel description, tongue and lip shapes as well as duration play great roles in identifying different vowel sounds. Duration alone can be a determining factor in distinguishing between two vowel sounds, for instance, between /i/ and /i˸/, or /ʊ/ and /u˸/. Not prolonging the sounds may be cause of embarrassing misunderstandings, to say the least.

Although aspects of vowel description have already been discussed (tongue shape, duration), an important factor remains to be discussed: whether the tongue and the lip shape are held constant or undergo change. In the following section we will be discussing phonemes produced when the tongue and lip shape suffer change.

Short vowels X Long vowels

By now, you might have a better ideia of the difference between long and short vowels. But after the following video, you’ll no longer have any questions!

LEARNING CHECK

ATENÇÃO!

Para desbloquear o próximo módulo, é necessário que você responda corretamente a uma das seguintes questões:

O conteúdo ainda não acabou.

Clique aqui e retorne para saber como desbloquear.

SECTION 2

To distinguish monophthongs from diphthongs

Tongue height, duration, and lip shape

So far we have studied vowels that do not change, that is, that are “pure”. They have been studied in terms of tongue height, duration, and lip shape.

Based on these categories, how can we describe the word choice?

Is it similar to its corresponding verb? Choose?

Or, are the categories not enough to account for the differences in the phonemes?

By now you may have become quite familiar with an important phonetics rule:

Spellings and phonemes do not coincide.

Trying to resort to the spelling of the words may be quite unsatisfactory, since both phonemes are composed of two letters, and both contain the letter o.

While the verb choose is composed of the long vowel studied before, that is, /u˸/, the noun choice is composed of a different vowel sound, called diphthong.

In this section we will be studying different diphthongs. Many varieties of English have several diphthongs.

Monophthongs and diphthongs

We called all the different long and short vowels studied in the previous section monophthongs, but so far we haven’t taken the chance to define them.

What makes a vowel a monophthong? – you may be asking yourself. And what makes it a diphthong instead?

These terms refer to the articulatory position during sound production.

When a vowel has only one articulatory position throughout its production, it is considered to be a monophthong. When, conversely, more than one articulatory position is observed, the vowel is then a diphthong.

In the word choose, for instance, the articulation is fixed throughout sound production; there is, then, no change in the position of the tongue or the lip.

In the word choice, however, two discernible different points are observed. It starts with an open vowel and ends with a close one. This diphthong /ɔi/ is a closing diphthong.

Pay attention: “For a sound to be considered a diphthong, the change – termed a glide – must be accomplished in one movement within a single syllable without the possibility of a break”. (COLLINS & MEES, 2013, p. 69)

The words choice, mouth and price are examples that contain pretty common diphthongs; they are all examples of closing diphthongs. They start with open vowels and raise to close vowels, in the area of /i/ and /u/.

Do you remember how close vowels are formed? Let’s recap!

Friendly reminder

To produce close vowels the tongue is kept in a higher position, near the roof of the mouth. Therefore, going from an open vowel to a close one involves tongue movement. As the tongue rises, to produce a close vowel, the space between the tongue and the roof of the mouth becomes narrower. Therefore, the tongue rises, closing the space between the roof of the mouth and the tongue.

Diphthongs can then be classed according to the direction of the tongue movement. There are closing diphthongs, as the ones discussed above, and centering diphthongs. In centering diphthongs the tongue moves towards the central vowel (/ə/). Closing diphthongs may also be classed into fronting and backing. In backing diphthongs the tongue moves towards a close back vowel (/ʊ/), in fronting diphthongs it moves toward a close front vowel (/i/).

Sum up

Fronting diphthongs end with /i/

Backing diphthongs end with /ʊ/

Centering diphthongs end with /ə/

FRONTING DIPHTHONGS - /ei/, /ai/, /ɔi/

/ei/

In this diphthong there is a combination of two vowel sounds, that is, /e/ and /i/. In fact, this is a compound sound, since the two vowels are blended. To produce this sound your lips should be spread and unrounded. Your jaw raises as your tongue moves. Your jaw closes slightly. The tongue moves from the midlevel position to being closer to the roof of the mouth. This diphthong is found in the beginning, middle and end of words. It may be represented by different spellings: a, ai, ay and eigh, as in the words:

late, main, day, eight

Now, pay attention to the following words:

bake, same, name, case

What do you notice? They are all formed by the same diphthong /ei/. But that is not the only characteristic they share. In all these words the letter a occurs in a syllable ending in silent e. Whenever this is the case, the letter a is pronounced as /ei/.

But let’s look at a different set of words:

reign, neighbor, vein

Whenever the letters ei are followed by g or n, they also represent the phoneme /ei/.

The letters ay, ai and ey are usually pronounced as /ei/ too. For instance, in the words:

play, away, they, aim

/ai/

Since this diphthong starts with /a/ and ends with /i/, the lips move from an open position to being slightly parted. The jaw also raises with the tongue and closes. This closing diphthong involves tongue movement. The tongue moves from a low position to a higher one. At the end, the tongue is closer to the roof of the mouth. It is, as the previous one, found in the beginning, middle and end of words. It is represented as different spelling patterns such as i, y, ie and igh. The following words contain the diphthong /ai/:

high, I, my, die

The words bite, refinement, fine also contain /ai/. But they have something else in common. The letter i occurs in a syllable ending in silent –e. And whenever this is the case, the letters are pronounced as /ai/. When the letter i is also followed by gh, ld and nd it represents the phoneme /ai/.

Examples:

sight, wild, find

/ɔi/

This diphthong may not cause many problems, as there are basically two different spellings for it: oy and oi. It starts with /ɔ/ and ends with /i/. That means that the lips move from a tense oval shape to a more relaxed position. As with the previous diphthongs, the tongue moves from a low position to a higher one. This diphthong is also found in the beginning, middle and end of words.

Examples:

oil, join, toy

Friendly reminder

Just remember that fronting diphthongs are types of closing diphthongs, since the phoneme is formed by going from vowels which are lower in the trapezium (meaning that the mouth is open, or, at least, slightly open) to a vowel which is in the higher end of the trapezium, that is, /i/. Also, /i/ is a front vowel and that is why /ei/, /ai/ and /ɔi/ are fronting diphthongs.

BACKING DIPHTHONGS – /aʊ/, /oʊ/

/aʊ/

Since this is a closing diphthong, the tongue glides from a lower position to a higher one. And to do that, your jaw also raises with the tongue, as you produce this sound. Your lips also glide from an open position. Just make sure your lips glide from a wide, open position to a closed one. If these lip and tongue movements do not occur, you will produce a monophthong instead. To produce a diphthong the articulatory position changes as you produce the sound, therefore, there is always lip and tongue movement. If your tongue and your lip remain in the same position throughout the sound production, the phoneme /a/ will be produced. You will be saying pond instead of pound, for instance, as we can hear below:

Pond instead of pound

In terms of spelling, this diphthong does not pose great challenges, as it is usually represented as the letter o followed by u, w, or ugh. Words that exemplify this diphthong are:

owl, mouse, loud, town, drought

/oʊ/

Let’s compare the two words coat and cut:

Are their pronunciation patterns similar or different? How similar or how different?

These words represent two different phonemes: a diphthong and a monophthong, respectively.

coat, cut

In the word coat, since it is a diphthong, there is a change in the articulatory position. The tongue glides from the midlevel position and comes closer to the roof of the mouth. The jaw also rises with the tongue. To produce this sound, your lips should also be kept tense and in a very rounded shape. Just make sure you round your lips into the shape of the letter o and prolong the sound. This is a long sound. It is found in the beginning, middle and end of words. And it may be represented by different spellings: o, oa, ow, oe, and ou; as in the words:

no, goat, know, toe, dough

The following words show a common pattern for this diphthong:

phone, home, note

What is it? What can you notice? The letter o is usually pronounced as /oʊ/ when it occurs in a syllable ending in silent e. Another common pattern is when o is followed by ld. In words such as bold, old, told the diphthong /oʊ/ is also present. Check it out:

bold, old, told

Just make sure you prolong the diphthong pronunciation to avoid misunderstandings.

CENTERING DIPHTHONGS - /iə/, /ʊə/, /eə/

/iə/

The diphthong /iə/ starts with the tongue position for /i/, that is, the tongue is in a higher position at first. Then, the tongue moves towards a centering position. This diphthong is usually spelled as e or ea.

Examples for this diphthong are the words:

near, fear, beer, dear, career, experience

/ʊə/

The diphthong /ʊə/ starts with the tongue position for the production of /ʊ/ and also moves towards a more centering tongue position. This diphthong is usually spelled as u, ou or oo. Differently from the phonemes previously discussed, this is not a common sound in English.

/ʊə/ is present in the following words:

during, hour, security

/eə/

In this diphthong, similarly to the previous two, the tongue also moves towards a mid-central position. To produce this phoneme, you start from the /e/ position and finish in a mid-central position, here represented as the phoneme /ə/. This diphthong is usually spelled as e or ea.

Examples:

care, hair, wear, air

Even though all the diphthongs have been represented by a combination of two symbols, for instance, /iə/, /ʊə/, and /eə/, they, actually, refer to a single phoneme, that is, they are single sounds. Diphthongs are also long sounds and they may be as long as the long vowels discussed in the previous section.

Comments

It’s no wonder, then, that in non-rhotic varieties certain diphthongs may be pronounced as long vowels instead.

Diphthongs are formed by tongue movement, and differently from cardinal vowels, they cannot be represented as a point in the vowel diagram. Diphthongs are thus vowels whose start point and end point do not coincide.

Now, bearing this in mind, let’s discuss two other words! The words fire and power.

fire, power

In both cases the end point and the start point are not the same.

However, these words entail a slightly different phenomenon.

Between the start point and the end point there is a third term, another vowel.

These are not separate sounds, since they refer to one single phoneme.

The words fire and power, then, may be examples of what is called triphthong. Alternatively, they may be called diphthong that have an extended vowel. Usually, these phonemes are represented by a diphthong followed by the letter r. The phonemes are as following: /aiə/ and /aʊə/.

Throughout this section we have discussed single phonemes that were actually a combination of two different vowels (or even three!). Two phonemes thus blended in order to produce a single long sound. While discussing centering diphthongs a phoneme gained importance, namely the mid-central vowel. This vowel, although presented in passing, is, actually, one of the most frequent sounds in the English language. In the next section, this mid-central vowel will be discussed in more details and you will learn that this neutral vowel, phonetically represented as /ə/, is much more complex and variable than this section showed. It is hence much more than a phoneme that just exists in combination with others.

Diphthongs

What is a diphthong, do you know? Stick around to learn more about this vowel sound!

LEARNING CHECK

ATENÇÃO!

Para desbloquear o próximo módulo, é necessário que você responda corretamente a uma das seguintes questões:

O conteúdo ainda não acabou.

Clique aqui e retorne para saber como desbloquear.

SECTION 3

To recognize the schwa sound

Context

Even though, grammatically speaking, English may pose fewer challenges to learners, especially when compared to a language packed with inflections such as German, the same does not apply, though, to its phonetics.

Trying to sound native-like may be cause of great frustration among learners. Eventually, they may lose motivation and just drop out of the course or just decide that they are not cut out for speaking the language.

English phonetics does not only influence the speech (how a student pronounces the sounds) but may also affect a student’s perception of sounds.

Many times, learners complain that a native speaker speaks too fast or that he or she does not pronounce all the sounds.

Time and again reality and expectation clash. There is a very simple reason for that.

Students expect phonemes (sounds) and graphemes (letters) to coincide.

OR

They expect letters to sound always the same, that is, to have a pretty definite pronunciation.

English is a language, however, that frustrates any attempt to establish a one-to-one relationship between phonemes and graphemes.

Do you remember that the letter a has seven different pronunciations? The words cat, cake and among contain three different phonemes associated with the letter a. And this is one of the great challenges English poses: many letters or even combination of letters may share the same pronunciation. Different words like about and doctor share the same phoneme, that is the schwa sound, even though their spellings do not coincide. What’s more, depending on the context in which a word is uttered, its pronunciation may change. In other words, when uttered alone it may be pronounced in a way, when the same word occurs in a sentence, however, it may sound differently. The context in which a phoneme occurs affects its pronunciation. The context may be a syllable, a phrase, or even a sentence.

In this section we will be studying a pretty common vowel sound. But don’t be mistaken! Common here just means ordinary, as this phoneme may be cause of some frustration.

The schwa sound: characteristics

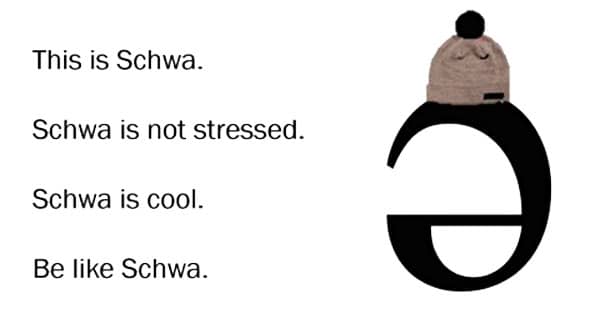

One of the most common vowel sounds in English is actually a “lazy sound”. Your lips should barely move to produce this phoneme, while they remain pretty relaxed. This is a quick, short sound, even shorter than the short vowels previously discussed.

It may appear:

And it represents many different spellings:

The letter a may be reduced to the schwa sound, as well as the letters e, i, o and u.

Similarly, the following combination of letters may also be reduced to the schwa: eo, ou, iou, io, and ai.

As you can see, basically all vowels can be reduced to the so-called schwa sound. The schwa sound has, then, no regular spelling. And this may be the reason why even some adult native speakers may find it hard to remember the spelling of certain parts of words.

Example

Calendar may be mistaken for calender; separate for seperate, just to name some examples of the correct and the wrong spelling.

This sound, nonetheless, even though it has no regular spelling and it can occur in different parts of words, owes its occurrence to certain circumstances. Notice that all along we have been using the word “reduced” to refer to the schwa. Vowels can be reduced to the schwa. The use of this word – reduced – can be a nice indicator of the context from which the schwa emerges.

But before discussing the contexts from which the schwa can emerge, let’s talk about a very simple word, the conjunction and.

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, this conjunction and can be pronounced in different ways, both in the American and in the British varieties. It has a strong and a weak form.

In its strong form it is pronounced as /ænd/.

In its weak form it may take two different pronunciations: /ənd/ and /ən/.

Both in American and in British English these forms are possibilities.

Now, pay attention to the vowels.

The vowels can be either /æ/ or /ə/; the same letter, but different sounds. The latter is what we call the schwa sound, which, as the Cambridge Dictionary points out, occurs in the weak forms of the words. In better terms, the schwa sound only occurs in unstressed syllables.

Stressed syllables have certain characteristics.

In the word teacher, for instance, the stress falls on the first part of the word (teach). In the word today, on the other hand, it falls on the second part (day). When nouns have only one syllable, then, this one must be stressed.

Unstressed syllables, conversely, are not as loud and not as long as stressed ones.

The second syllable in teacher is thus shorter and lower.

That is why we say vowels can be reduced to the schwa sound. Whenever vowels, any vowels, find themselves in unstressed syllables they may be reduced to the schwa sound.

Just remember:

- The schwa only occurs in unstressed syllables.

- It is the most common vowel in connected spoken English.

- It has no regular spelling.

- It is a mid-central vowel, sometimes called neutral vowel.

Regarding the connection between the symbol, /ə/, and the sound, Richard Ogden claims:

Its precise quality is highly variable, partly because it is very short and strongly coloured by neighbouring consonants; this is one reason why a ‘float’ symbol, with no precise definition, can be a useful tool for transcription: it can cover a wide range of qualities in one symbol.

(OGDEN, p.62)

The schwa, however, is not only variable within words, but also within phrases and sentences.

Let’s see some more examples!

Within words

- The schwa may be found in the beginning of words, as in:

ago

amaze

suppose

contain

umbrella

upon

- In the middle of words, as you can see in:

agony

relative

holiday

company

telephone

- At the end of words. For example, in:

soda

sofa

lemon

circus

- And also more than once in a word (since more than one syllable may be unstressed), such as in:

umbrella

elephant

accident

As you could see, it can be represented by different spellings:

Attention

Combinations of letters such as eo, ou, iou, io, and ai may also be reduced to the schwa, as is the case with the following words: pigeon, famous, religion, certain, delicious, nation.

As you can see the schwa sound is a common vowel sound because many different letters and combinations of letters can represent it. It is common but, by no means, simple! It may not even be represented at all!

Let’s consider the word rhythm!

It has two syllables but only one discernible vowel, right?

Actually, that is not right. The word rhythm has two syllables and two vowels. The first vowel is stressed, the vowel /i/. The second one, since it is unstressed, is pronounced as the “lazy sound”, that is, the schwa /ə/.

That is wrong! It has two syllables and two vowels. The first vowel is stressed, the vowel /i/. The second one, since it is unstressed, is pronounced as the “lazy sound”, that is, the schwa /ə/.

Can you see how English spelling can be misleading? Nothing in the spelling of the word shows this second vowel. It is, however, there, even if only as a quick, short, relaxed sound.

Within phrases and sentences

As mentioned before, the conjunction and may be pronounced in different ways. Two vowel phonemes are possible: /æ/ and /ə/

But why is that?, you may be asking yourself.

The reason why lies in the context from which the word emerges.

Words within sentences have different stress patterns. While some words may be emphasized, that is, they are pronounced on a different pitch and are usually louder and longer; others may be barely pronounced.

Some, depending on how the speaker articulates the sounds, may seem to completely disappear. Stress, in English, points out to the most important words in a sentence or phrase.

By emphasizing some words, you are signalling to your listener that some words are more important to the message being conveyed than others.

The conjunction and alone may be pronounced as /ænd/. Within a sentence, however, since it carries little meaning, its vowel may be reduced to a schwa sound.

Vowels in grammatical words, or function words, thus, may be reduced to the schwa sound.

In this pretty common saying: “An apple a day keeps the doctor away”, the schwa sound may be found within words and within the sentence.

The unstressed syllables in the words: apple, doctor and away, all have the schwa sound.

The second vowels in the words apple and doctor are pronounced as the schwa sound, as well as the first vowel in away.

Within the sentence, the articles an, a and the, since they are unstressed, also contain the schwa sound.

When you analyze this pretty common saying, you see how the schwa sound is an ordinary sound:

An apple a day keeps the doctor away

ən 'æpəl ə 'deɪ 'ki:ps ðə 'dɒktə ə'weɪ

Grammatical words – conjunctions, determiners, auxiliaries, prepositions – whenever their function in a sentence is mainly grammatical have their vowels reduced to the schwa sound. In the noun phrase a glass of water, both the article a, and the preposition of are reduced to the schwa sound. In the question – Do you like music? – the auxiliary do is also reduced to the schwa sound.

Friendly reminder

Just remember that do can be an auxiliary verb and a main verb, it can also be emphasized or not. Therefore, the occurrence of the schwa is here conditioned by whether or not the word do is stressed. When it is stressed, it may be pronounced as a short vowel or a long vowel; when, on the other hand, it is unstressed, then it is pronounced as a schwa.

Strong and weak forms

As mentioned before, the auxiliary verb do can be stressed or unstressed, depending on the context where it occurs. Other auxiliary verbs also have weak and strong forms. In their weak forms they are pronounced as the neutral vowel schwa.

Let’s compare two utterances:

a) Was she reading?

b) Yes, she was.

Even though examples a and b show the same auxiliary verb – was – in letter a, was appears in its weak form, whereas in b, it is in its strong form. The schwa sound, as it only occurs in unstressed syllables, is only present in the weak forms of auxiliary verbs. In short answers, auxiliary verbs (do, does, have, has, were and even the modal verb can) appear in their strong forms. In questions, however, the weak forms (the schwa) are prevalent.

Example:

Since the schwa sound is one of the most frequent sounds in the English language, understanding how it is pronounced and when and where it occurs may help a learner speak as naturally as possible. The schwa sound is an important indicator of unstressed sounds, both within words and sentences. This “lazy sound” is not at all sloppy and it occurs naturally in all types of settings, be them formal or informal. By practicing this short, relaxed sound, you will sound more and more natural in English.

The schwa sound

What is the most common sound in the English language? Do you know? No? Watch this video to learn more about the “lazy sound”!

LEARNING CHECK

ATENÇÃO!

Para desbloquear o próximo módulo, é necessário que você responda corretamente a uma das seguintes questões:

O conteúdo ainda não acabou.

Clique aqui e retorne para saber como desbloquear.

SECTION 4

To describe concepts linked to the combination of vowels and consonants (tonicity, intonation, homonymy and polysemy)

Combining vowels and consonants

Although we may claim that someone has a monotonous tone of voice, as if this person were speaking in a monotone, that is, in one single tone from beginning to end; in reality, this perception couldn’t be further from the truth. We are incapable of utterances that are monotone in nature. We are actually using pitch variation all the time.

Certain sounds may be emphasized,

while others may be unstressed.

Certain phonemes may be longer and louder,

while others may be quick and lower.

We, therefore, inflect our speech all the time. The objective of this section, then, is to look a little deeper into such inflections, such intonational contours.

So far we have been discussing different types of phonemes. However, whether we discuss long or short vowels or even diphthongs, these sounds do not exist in isolation, but rather they exist combined in syllables and, consequently in larger structures: sentences, clauses, texts.

In this section we will be delving into some concepts which were discussed in passing, namely the syllable, stress, tonic syllables and intonation.

The syllable

We have seen that vowels are syllabic phonemes, meaning that they can form a syllable on their own. We have also seen that the schwa sound only occurs in unstressed syllables. And while we have brought the term syllable into the discussion, we haven’t taken the time yet to define or even discuss what constitutes a syllable.

In a nutshell, a syllable has two main constituents: the onset and the rhyme.

The onset is defined as any consonant that precedes a vowel. In a word such as clip, two consonants precede the vowel (/k/ and /l), whereas in a word such as it, the onset slot is empty. A word then in English may have an empty onset. The remaining segments constitute the rhyme.

The rhyme in the word it is /it/, in the word clip, /ip/. The rhyme can be subdivided into nucleus and coda. The most sonorous element in a syllable will occupy the nucleus slot. Low vowels, high vowels, approximants, nasals may be fit to occupy the nucleus slot, in this respective order. So, in the words it and clip the phoneme /i/ occupies the nucleus slot.

In a word such as appraise two vowels are identifiable. The phoneme /ə/, and the diphthong /ei/.

These vowels constitute two different nuclei. This is then a two-syllable word. When a word in English has more than one syllable, one of them receives more stress than the others. In other words, the amount of volume a speaker gives to one of the syllables is greater than to any other.

Stressed syllables are louder and longer. In the word appraise the use of the schwa sound is a good indicator that the first syllable is the unstressed one. Sometimes words such as stress, accent or emphasis are used interchangeably.

The stress may fall on the first syllable, in words such as: Tuesday, awful, ever, brother, window. It may fall on the second syllable as is the case in words such as: myself, outdone, around, allow.

Words containing more than two syllables, have primary stress on the first, second or third syllables. Since English makes use of strong and weak stress, one of the syllables is going to be more emphasized than the others.

In a word such as afternoon, primary stress falls on the third syllable.

In a word such as vanilla, primary stress will fall on the second syllable.

Stressing the wrong syllable may lead to a bunch of misunderstandings and communication problems.

A common mistake Brazilian students make is to incorrectly stress the first syllable in the word police, when, primary stress should fall on the second syllable.

Tonic syllables

Stress goes beyond the boundaries of word level. Within sentences and clauses different words receive different amounts of emphasis. It would sound extremely unnatural to stress all the words equally in a sentence. Stress is a great tool in communication. By stressing some words, the speaker highlights the importance of these words within the sentence. If, on the other hand, stress is placed on the wrong word you may not only completely change the meaning of the sentence, but also distort the intended meaning or even give much stress to unimportant words.

Let’s compare two different utterances.

He lives in the green house.

He lives in the greenhouse.

In the first example, the word house is being stressed, meaning that his house is green.

If stress is placed on green, instead, like in the second example, the meaning conveyed is another. He lives then in the place where the plants grow.

Tip

Content words or lexical words, such as nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs are usually stressed. Grammatical words such as auxiliary verbs, determiners, prepositions, conjunctions are usually unstressed.

In a sentence or clause certain words will be more stressed than others. Stress will fall more often than not on content words, unless stressing grammatical words may serve a purpose in conveying meaning. For instance, in the following sentence:

I do like reading.

The auxiliary verb may be stressed to oppose a previous utterance and to emphasize the fact that even though you might believe reading is not one of my favorite pastimes, I actually like it a lot. Thus, stress may fall on auxiliary verbs to correct some false assumption. Stressing words, then, helps clarify meaning by calling attention to certain words.

In the following sentence:

Mary went to the doctor.

Three content words can be perceived – Mary, went and doctor. These words, this way, are more stressed than the grammatical words – to and the. The content words also have stressed syllables. The penultimate syllable in Mary, went (since it is a single syllable) and the penultimate syllable in doctor. There is one syllable, however, in the whole sentence that is more prominent and longer than the others. This syllable is called the tonic syllable, where the tone falls.

According to Philip Carr:

[tone] is the extra pitch movement placed on that syllable. In our example, the tone is a falling tone: the rate of vibration of the vocal folds decreases as the syllable is uttered, resulting in a transition from a higher to a lower pitch.

(CARR, 2013, p. 131)

This falling tone is typical of declarative utterances.

Intonation

Simply put, intonation refers to the rise and fall of the voice when speaking. Intonation conveys meaning, the speaker’s attitude, signals to whether the utterance is a question or a statement, etc. The wrong use of intonation, if your voice rises instead of falling, for instance; may change a declarative sentence into a question. If, on the other hand, your voice stays the same, instead of falling or rising, you may come across as being bored or uninterested.

- Two types of sentences may end with a falling pitch:

Declarative sentences, as mentioned before.

Example:

She is my sister. / Mary is a doctor.

Questions starting with question words (what, who, where, when, etc).

Example:

Where’s my book? / When did he leave?

- As examples of rising pitch we can mention:

Yes/ No questions

Example:

Are you a doctor? Is she coming?

Statements that express doubt or uncertainty.

Example:

I think they are coming.

There may also be combinations of rising and falling pitches. The use of the rise-fall tone, when the pitch rises and then falls, may convey certainty, exclamation, or strong conviction on the part of the speaker. Conversely, a fall-rise tone, when the pitch falls and then rises, may convey hesitation, lack of certainty or reservation on the part of the speaker (CARR, 2013).

Homonymy and Polysemy

All along we have been harping on the same string. We keep insisting on the fact that English is a language in which a one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds does not exist. Perhaps a one-to-many or many-to-one correspondence would be more realistic. Homophones and homographs are those types of phenomena that once again break the illusion that graphemes and phonemes can actually coincide.

HOMOPHONES

Homophones are words that are pronounced the same, so they have the same phonemic transcription, but that are actually spelled in different ways. Example to this phenomenon is the pair: grown and groan. More than two words may also be involved. The following words are all pronounced the same, that is, as /sait /. The words are: sight, site and cite.

HOMOGRAPHS

Homographs are words that are spelled the same but pronounced differently. There are many nouns and verbs in English which are written in the same way. Their only difference resides in the stressed syllable. Conflict, for instance, can be either a verb or a noun. The stress for nouns will always fall on the first syllable, whereas for verbs the second syllable will be stressed.

There are many two-syllable nouns and verbs that fall under this category, examples to this case are:

conflict, conflict

conduct, conduct

content, content

desert, desert

digest, digest

contest, contest

permit, permit

object, object

exploit, exploit

increase, increase

Can you see now why stressing the right syllable can have huge impact on the meaning?

Comments

If English had a regular spelling system, homophones and homographs would not exist. But as we can see, this is definitely not the case.

In English we can also find full homonyms. These are words which are spelled the same, pronounced the same, but that have completely different meanings.

Let’s think of the word left! Left can be both the opposite of right (direction) and the past tense of the verb leave. Both words even though they share the same spelling and pronunciation have completely unrelated meanings. They are, then, full homonyms.

Attention

Homonymy, however, should not be mistaken for polysemy. Polysemy refers to the same word being applied to different contexts. In better terms, the word can have literal meaning and extended metaphorical meaning.

One example would be the word head, which can refer to both a part of the body, or to the position of the boss, like in the phrase: head of the department. Polysemy, then, refers to the same word used in two different ways: literal and metaphorical.

But, let’s analyze the following sentences:

I read the newspaper this morning.

The newspaper fired Jill.

These two sentences are clear examples of polysemy since they entail the exact same word – newspaper – being used differently. In sentence a) it refers to the actual object and, in sentence b), to the company. The word good, since it can refer to both moral judgment and the judgment of a skill, can also an example of polysemy.

However, when we say that: my dog always barks at the mailmen and we compare this sentence to: the tree’s bark was brown; we realize that even though the same word is being used, that is, bark, it refers to two different things. In the first sentence, it refers to the sound a dog makes, whereas in the second one, it refers to the exterior of a tree. In the above examples, the words have the same spelling and pronunciation, their only difference resides in meaning. This is then a clear case of homonymy.

Summing up, phonetics plays a great role in conveying meaning. By means of the correct use of stress and intonation, misunderstandings can be avoided and communication will run more smoothly. What’s more, being attentive to the correct stress of words, whether primary stress falls on the first, second or third syllable, can avoid mistaking a homograph for the other. Since English does not have a one-to-one correspondence between graphemes and phonemes, phenomena such as homophones and homographs are quite common. The latter refers to words that share the same spelling but whose pronunciation differ. Stress, then, can help distinguish one homograph from the other.

Even though homonymy and polysemy may at first seem synonymous, they actually refer to two different situations. The former is when two completely different words share the same spelling and pronunciation. And the latter is when the same word is used in different contexts.

Vowels and consonants.

What do you know about syllabification in English? Let's learn more about how syllables are formed in English!

LEARNING CHECK

ATENÇÃO!

Para desbloquear o próximo módulo, é necessário que você responda corretamente a uma das seguintes questões:

O conteúdo ainda não acabou.

Clique aqui e retorne para saber como desbloquear.

CONCLUSION

FINAL ISSUES

We have studied that vowels in English are described based on tongue and lip shapes, duration and articulatory positions. Vowels can be long or short, monophthongs or diphthongs and also open or close. We have also learned that stress and intonation play significant roles in conveying messages. And finally, since spelling and pronunciation do not coincide, we have studied different phenomena that show how this is actually true.

By now you may have become familiarized with how vowels are produced in English, and you may also have learned to distinguish different vowel sounds and identify different phenomena such as homonymy and polysemy.

Podcast

Let’s hear now Professor Tatiana Massuno explaining, in a summarized way, what we studied throughout these four sections

ACHIEVEMENTS

You have reached the following objectives:

To identify different vowel phonemes: short and long vowels.

To distinguish monophthongs from diphthongs.

To recognize the schwa sound.

To describe concepts linked to the combination of vowels and consonants (tonicity, intonation, homonymy and polysemy).