Description

Phonetic and phonological aspects of the English language.

Purpose

Knowing the main principles of English Phonetics and Phonology and their application to the language study is very important for its good oral communication and teaching.

Goals

Section 1

To recognize the concepts of phone, phoneme, and grapheme

Section 2

To identify principles of linguistic variation

Section 3

To describe functions and classifications of the International Phonetic Alphabet

Warm-up

In this unit we present a brief discussion on important concepts in the fields of Phonetics and Phonology for a better understanding of the English oral and written discourses.

Firstly, we discuss two concepts that can sometimes cause a lot of trouble in language teaching: phoneme and grapheme (letter). Knowing about their similarities and differences is important for several reasons but particularly because it may lessen difficulties in written production in first or second language (L1 and L2).

Secondly, we present a discussion about matters in spoken and written languages regarding the various forms of expressions that materialize linguistic variation, discussing the heterogeneous character of languages. Then we bring up how the awareness of this subject can be particularly significant in teaching/learning first language writing or studying a second one.

Finally, in section 3, we discuss the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), showing how it represents the speech sounds of any language, allowing accuracy in phonetic/phonological description, including linguistic variation whether in an L1 or L2.

Section 1

To recognize the concepts of phone, phoneme, and grapheme

Phonetics X Phonology

Let us begin our discussion by defining two concepts that we wish to deepen:

What is Phonetics and what is Phonology?

Despite being intrinsically complementary, Phonetics and Phonology are distinct areas of linguistic investigation. Phonetics has a more descriptive nature and is the area in Linguistics that presents the methods for description, classification, and transcription of sounds of human speech, that is, of any language. Phonology, in turn, has a more explanatory and interpretative nature and is traditionally understood as the area that studies phonemes: the functional sounds of speech from the point of view of the language system. Phonology studies the sounds that are in opposition in a particular language: their functions in the system.

Phonetical and phonological studies, respectively, focus on the descriptive material of the sounds of human speech and on the cognitively internalized linguistic-phonological knowledge.

Phonetics is dedicated to the description of the phones: the actual speech sounds that speakers produce, and listeners hear, resulting from the performance of a complex articulatory/phonatory apparatus.

Phonology is dedicated to the description of phonemes: the mental representations of a specific speech sound, our phonological knowledge, that emerge cognitively despite the possible various actual phonetic realizations related to a same phoneme.

For the production and perception of natural languages, people access a set of Articulatory mechanisms that are ultimately responsible for the formation of the phones, the units of sounds, devoid of meanings, that are the concrete material of any linguistic system. Thus, Phonetics investigates and describes the smallest information produced and perceived throughout the current production of a natural language. Phonetics is responsible for observing aspects related to the way such information is transmitted from physical properties (Acoustic Phonetics), the way they are perceived (Auditory Phonetics), and the way they are produced (articulatory Phonetics).

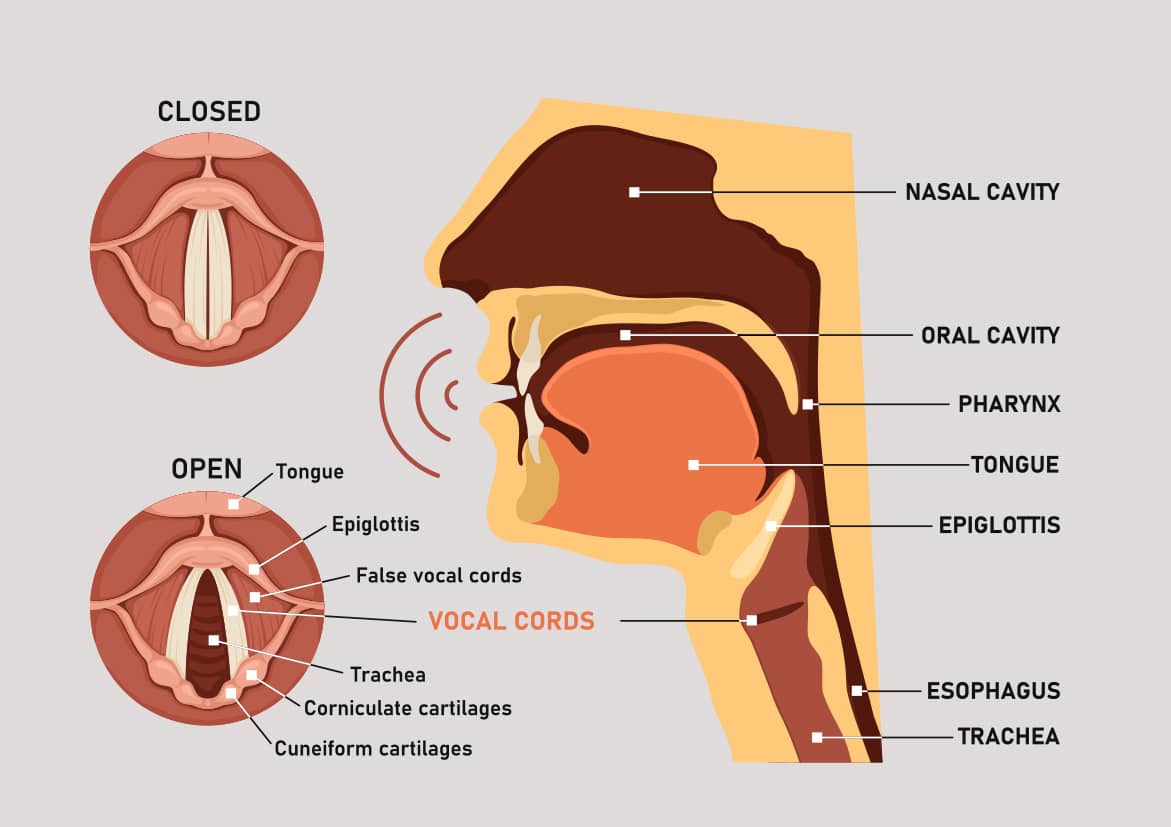

What we call complex articulatory/phonatory apparatus is a set of human body parts responsible for producing the different speech sounds. Since the release of the airstream from the lungs, as it goes through the larynx to mouth or nostrils, distinct parts of the body act, and different processes take place. The picture below shows the body parts activated in speech sound formation:

From the interaction of the parts of the complex articulatory/phonatory apparatus, a limited number of segments is formed. These segments are the minimal units of speech, objects of study in Phonetics. These segments are consonants or vowels.

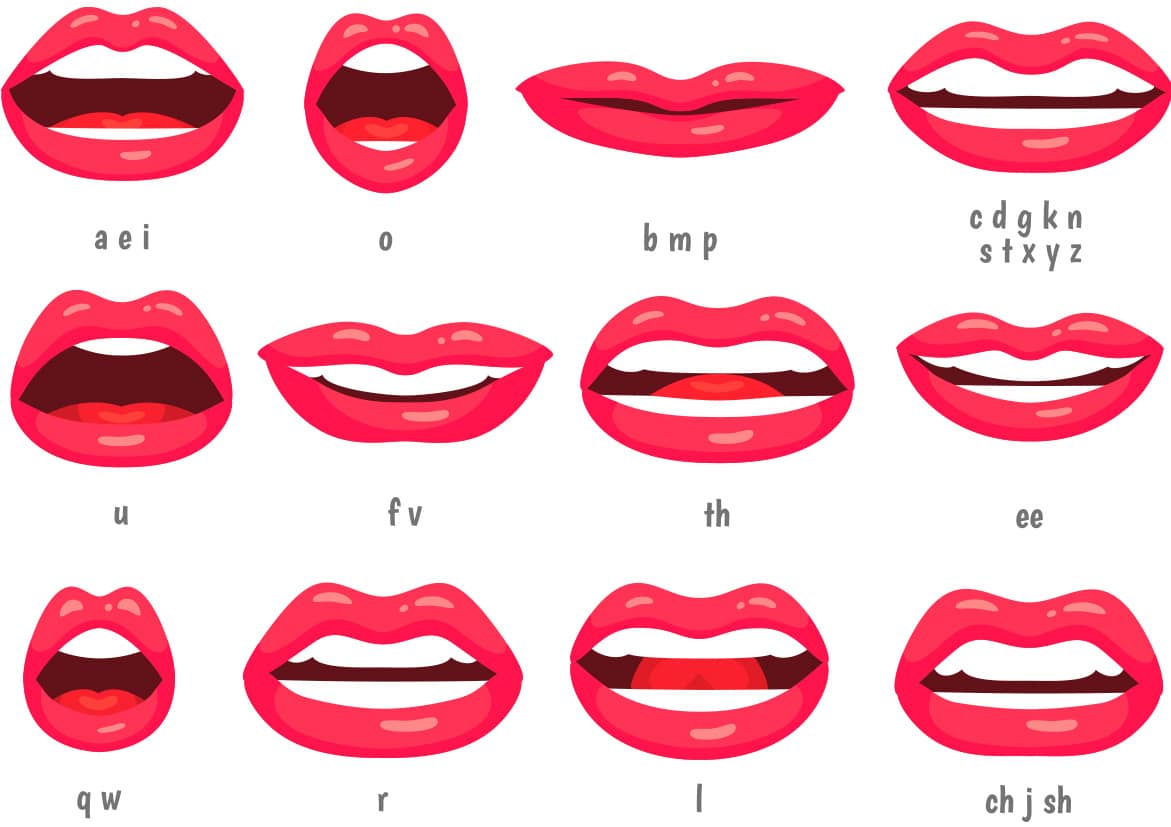

In the production of consonant and vowel sounds, we see the interaction of factors that together make up what we can call the segmental identity of the sound, which we have technically identified as the phone. Consonants and vowels may be differentiated by the way they are produced, concerning the airstream flow.

Consonants present some constriction during the airstream release, and they are formed from the interaction of three aspects:

Manner of articulation

Different ways airstream flows from the lungs out of the oral or nasal cavities.

Point of articulation

Different Articulatory locations in the course of sound production.

Voicing

The role played by the vocal folds (glottis) in the production of voiceless or voiced sounds.

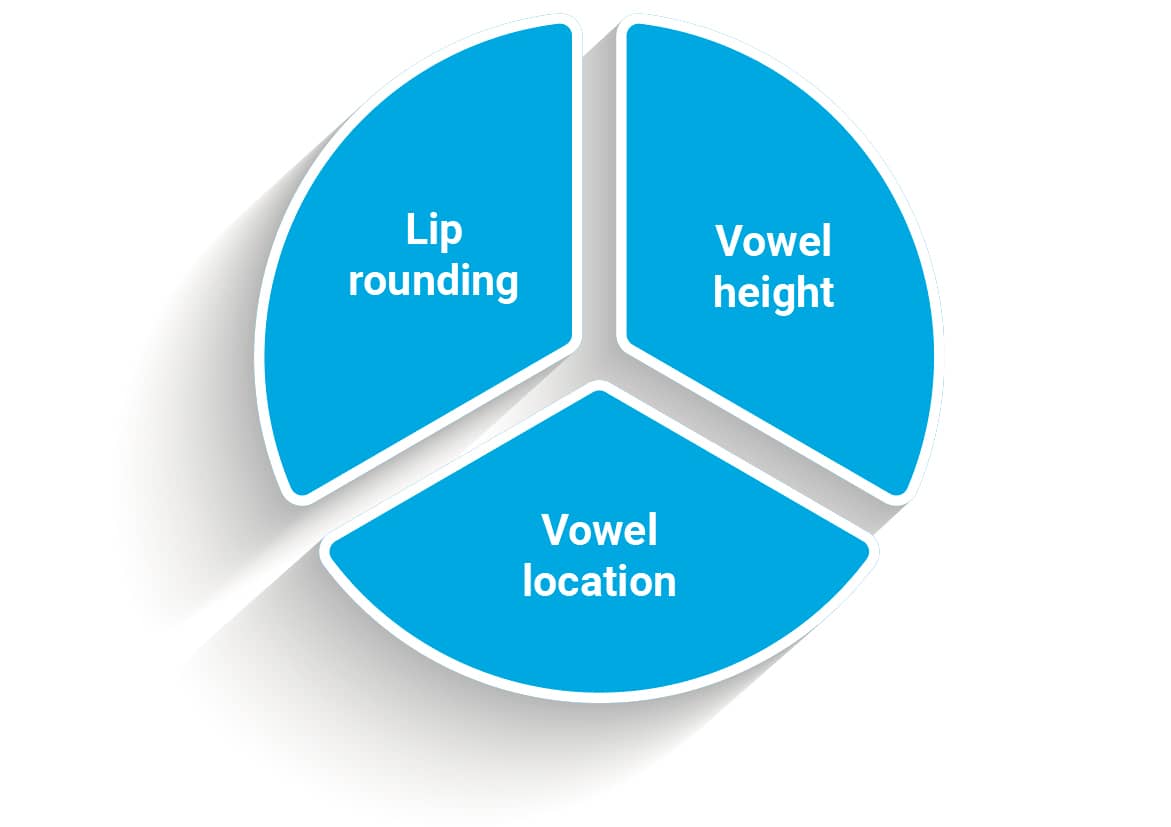

Vowels are formed with no constriction during the airstream release. They are voiced sounds by nature and formed from the interaction of the three following processes:

Vowel height

The greater or lesser verticality of the tongue height.

Vowel location

The greater or lesser horizontality of a certain section of the tongue.

Lip rounding

The roundness of the lips that can be more or less rounded at the time of production.

Manner and point of articulation, voicing, lip rounding, vowel height and vowel location are the most commonly used features in structuralist phonetic descriptions in general. In this perspective, a segment can be transcribed from the identification of its set of features. For example, the sound [p] can be identified as the plosive, bilabial, voiceless consonant, and the sound [i] as the high, front, unrounded vowel.

Comment

The charts of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), to be presented in Section 3, describe the list of consonants and vowels so far discovered in at least one of the known human languages. In this representation, consonants are described and organized based on the interaction of the voicing, manner, and point of articulation features, while vowels are described and organized based on the height, location, and lip rounding ones.

Phonemes

The first phonological concept we need to highlight is the phoneme. Not every phone is present or has the function of a phoneme in a language. Phones only have the role of phonemes in a language when they have a contrastive function, which means that they cause changes in lexical meaning.

If Phonetics is concentrated in the description of speech sounds, Phonology, on the other hand, is interested in the internal relations shared by the phonemes of a same linguistic system. In opposition to the more concrete nature of the phone, the notion of phoneme points to its role and function of determining differences in meanings between words within a same linguistic system. The phoneme becomes the smallest phonological unit of the language. But, being constituted by the distinctive features that simultaneously define it, not only the phonemes themselves, but mainly the properties that constitute them, would be the primitives of the phonological studies of any language.

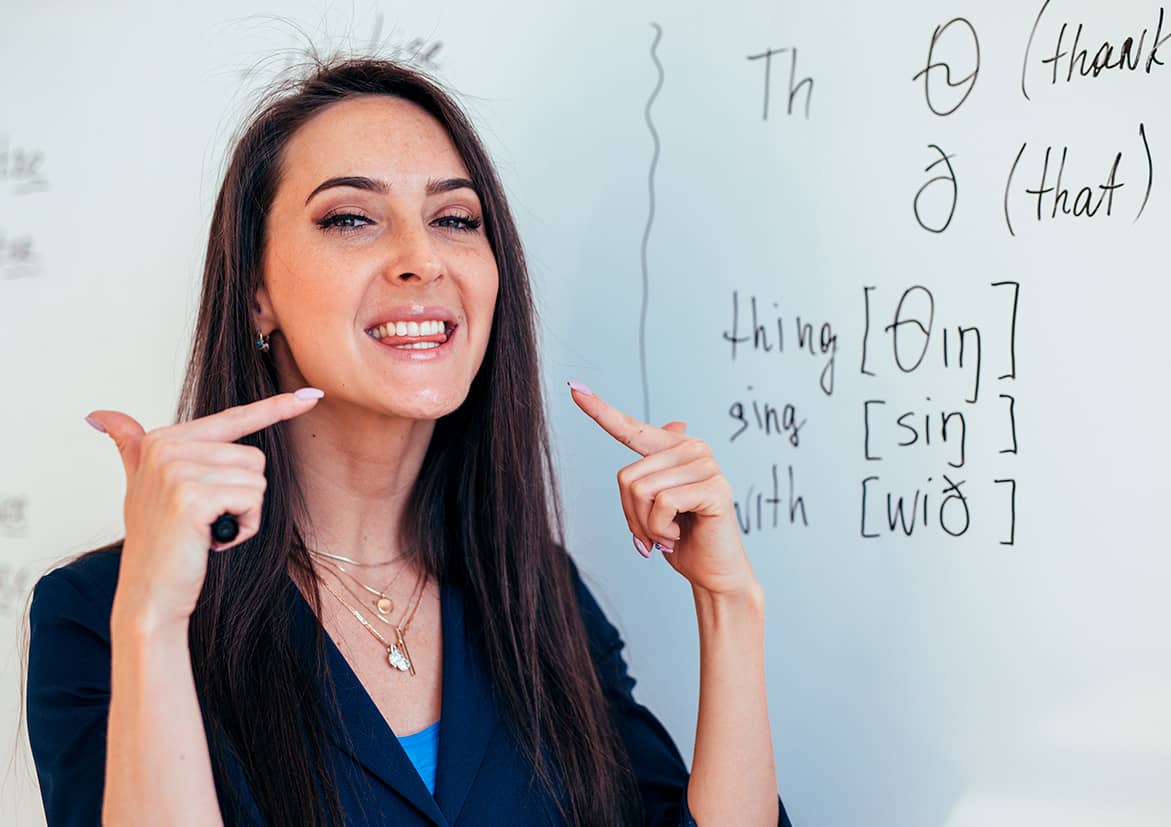

Phonemes are therefore opposing sounds within the same linguistic system, so that the change of one phoneme to another implies a change in the meaning of words, as we see in the minimal pairs think/sink and sin/sing presented as follows:

Minimal pairs

Pair of words that differ on a single phoneme.

/θɪŋk/ - /sɪŋk/

/sɪn/ - /sɪŋ/

We see that the phonemes /θ/ e /s/ as well as /n/ and /ŋ/ establish meaning relations between lexical items, due to differences between the features that constitute them. In both the first and the second pair of phonemes, the only difference regarding the sounds is related to the point of articulation, with the other features being preserved with no differences. Such phones function as elements that guarantee the word distinction in English and are therefore classified as phonemes.

The identification of minimal pairs results from a minimal pair test. Whether a phone has phonemic status in a language or not, the minimal pair test must be carried out.

But, wait – what is the minimal pair test?

Basically, we replace one phone by another in the same phonetic context and see if different lexical items are then identified. Minimal pairs are the structural evidence that identifies the distinctive elements of a given language, that is, its phonemes.

Phonology deals with the relationship between realization and perception of segments and shows how information is cognitively stored. In this sense, phonemes are cognitively stored as distinctive units of words and, although we pronounce a phoneme with slightly different phonetic characteristics in certain contexts, we do not fail to identify it as a same abstract unit.

Learn more

Although the surrounding phonetic context may influence the Articulatory characteristics of the segments, such differences are not necessarily important to make lexical distinctions, since the phoneme, the cognitive phonological knowledge, will always be the same. In English, for example, in the initial phonetic context, as in <pin>, the phoneme /p/ is aspirated, which no longer occurs in the non-initial phonetic context, as in <spin>, in which it is pronounced in its full form. Still, in the end of a syllable, as in <stamp>, /p/ may not even be pronounced, articulated, which does not mean that it will not be cognitively accessed, which is evidenced by its graphic representation in the written language, for example.

Graphemes and phonological knowledge

It is important to observe the role of phonological knowledge in the development of writing in an L1 or L2. Spelling register does not always reflect spoken language, and the mistaken association between phonemes and letters may create important difficulties for those beginning to delve into the writing world both in the first or the second language. For educational purposes, it is worth observing that spelling mistakes may be strongly motivated and explainable, if we take L1/L2 phonological knowledge interference into account.

The nature of the grapheme differs from that of the phoneme and this is extremely important to be taken into consideration when it comes to teaching and to L1/L2 literacy development.

If phonemes are the sounds that differentiate words in a language, graphemes can be defined as the graphic signs used for the representation of the sound system of a language in the writing. Phonemes and graphemes are distinct linguistic realities: the former stands for the psychological reality of the minimal units of a language and the latter stands for the graphic representation of the sounds or, at least, for an attempt of this representation, since writing will not always be able to reflect the abstract and cognitively stored sound.

The writing process can be affected at different levels due to the greater or lesser degree of impact of phonological knowledge of the oral L1 or L2. Both writing in L1 and L2 can be hindered, for example, by the differences between the number of phonemes in a word and the number of letters that make up its orthographic representation. It is important for the professional who comes to work with learners of a written language to understand these issues, because some degree of phonological knowledge may always make writing development even harder.

A good example on this issue is the differentiation between the phonological knowledge regarding the words <strength> and <length> and their orthographic representations. The following tables deal with this point. In the top line, we have the orthographic representation of the word and its number of letters. In the next line, we have the possibilities of phonetic representation of these words in English, and in the last line, the phonological representation, which cognitively encompasses all the possibilities of varied uses of these words by the speakers of that language:

| Orthographic representation | <strength> (7 letters) |

| Phonetic representation | [st̠͡ɹ̠ɛŋkθ], [st̠͡ɹ̠ɛn̪θ] (7 or 6 phonemes) |

| Phonological representation | /stɹɛŋkθ/ |

| Orthographic representation | <length> (6 letters) |

| Phonetic representation | [lɛŋθ], [lɛnθ],[lɛŋkθ], [lɛntθ] (4 or 5 phonemes) |

| Phonological representation | /leŋθ/ |

The examples show the difference in distribution of letters and phonemes as a possible difficulty factor for the learning of writing due to linguistic transfer. Also, it is worth noticing that for both words more than one form of pronunciation is found, which points to cases of linguistic variation, i.e., the possibility that different individuals, organized under different social circumstances, produce such words in different ways. This fact illustrates how the teaching-learning writing process may be even more complex.

Sounds and graphemes do not always match in a systematic way. One sound can be represented by different letters, the same spelling may refer to different sounds or there may be ‘’silent’’ letters that are not pronounced at all. As we will see in section 3, a separate spelling system, a phonetic alphabet in which each symbol corresponds to one and only one phoneme, is necessary to universally describe the pronunciation of words of any language in a precise manner.

Let’s review the main points concerning Phonetics and Phonology:

CHECKING LEARNING

ATENÇÃO!

Para desbloquear o próximo módulo, é necessário que você responda corretamente a uma das seguintes questões:

O conteúdo ainda não acabou.

Clique aqui e retorne para saber como desbloquear.

Section 2

To identify principles of linguistic variation

Linguistic variation

In the early 1960’s, William Labov conducted a major investigation into English spoken on the island of Marthaʼs Vineyard in Massachusetts, United States. Later, Labov develops a study of the same nature, with the dialect spoken in New York City. In both studies, the researcher had a single and important objective: to show the crucial role of social factors in explaining linguistic variation. This is where Variationist Sociolinguistics emerges as an area of investigation and research in Linguistics.

The author realizes that the variation in linguistic uses of similar functions and meanings was in fact highly controlled and organized by factors associated to the social profiles of speakers and by internal linguistic factors. Nowadays, studies on linguistic variation are extended to the different contexts of language use, whether spoken or written, seeking to identify factors implicit in the options of one or another way of saying/writing something.

Based on Labov's studies, the idea that linguistic variation is random and not systemic is overcome.

The idea that language variation would be ordered becomes a counterpoint to the thought that language is structurally organized in spite of its speakers and its diverse uses. Linguistic variation comes to be understood as a non-random object that could be well explained by the existing correlation between linguistic and nonlinguistic social factors.

Sociolinguistic variationist practice shows that the supposed linguistic homogeneity, predicted by Saussure's structuralist perspective, could be questioned by the idea of systematized heterogeneity: a fact verifiable in any natural language which shows that variation is controlled and strongly conditioned by factors inherent to the language and by external social ones. There is therefore a probabilistic dimension in language variation: a tendency for certain uses to occur in certain communicative contexts thanks to the action of this set of factors.

Phonological linguistic variation is thus important for the description of languages. The following examples show at least more than one way of saying the same word in English. In each case there may be a set of internal and external factors controlling each choice:

Body

[ˈbɑːdi] ~ [ˈbɑːɾi]

Hold on

hol[d] on ~ hol[Ø] on

Saturday

[ˈsætədeɪ] ~ [ˈˈsætɚdeɪ] ~ [sæɾəɾeɪ]

The different ways of pronouncing the words <body>, <hold on> and <saturday> can be explained by internal factors linked to the linguistic context in which they are used in interaction with external social factors, such as the region where the language is spoken, the social group, the register etc. In the end of the day, what we observe is that a single phoneme may be realized differently according to these intrinsic and extrinsic factors with no cognitive jeopardy.

Summing-up

In other words, a phoneme can be realized as different phones. The English /p/ sound can be produced as the aspirated [ph], in its full form with no aspiration [p] or without audible release [p']. In all of the cases the sound is interpreted as a unique phoneme: the English /p/ sound.

Allophones

The phones that are realizations of the same phoneme are called allophones. Thus [p], [ph] and [p'] are allophones of the phoneme /p/ in English. The distribution of the allophones of a phoneme in speech is usually complementary. This means that each allophone occurs exclusively in one specific phonetic context. This is the case for the phoneme /p/ allophones in English. The complementary distribution of /p/ allophones can be described by phonological rules:

- aspirated [ph] occurs when it is the only consonant at the beginning of a stressed syllable, as in the word picture.

- [p'] occurs before other plosives, as in the word captain, or at the end of an utterance.

- [p] occurs in other positions, as in the word spin.

In English, the regular verbs in the simple past end in “ed”, but they will be differently pronounced depending on the linguistic context surrounding it. There are three different ways to pronounce the /ed/ ending of regular verbs: [id], [t] or [d]. The different pronunciation depends on the preceding sound, the one at the end of the infinitive form of the main verb. If the preceding sound is /t/ or //d/ the /ed/ phoneme will be /id/. If the preceding sound is a voiced sound, it will be pronounced /d/ and if it is a voiceless sound it will be pronounced /t/.

The following chart illustrates that:

/id/ |

/d/ |

/t/ |

| needed | lived | shopped |

| hated | tried | picked |

The English -ed endings may be considered to be a case of allophony in this language, however it is also considered a case of allomorphy, but that is not of our interest in this class. The same holds true regarding the plural forms in English. If English -ed endings for phonological reasons change into /id/, /d/ and /t/, something similar occurs with the plural /S/ which changes into /z/, /s/ or /ez/ depending on the preceding sound.

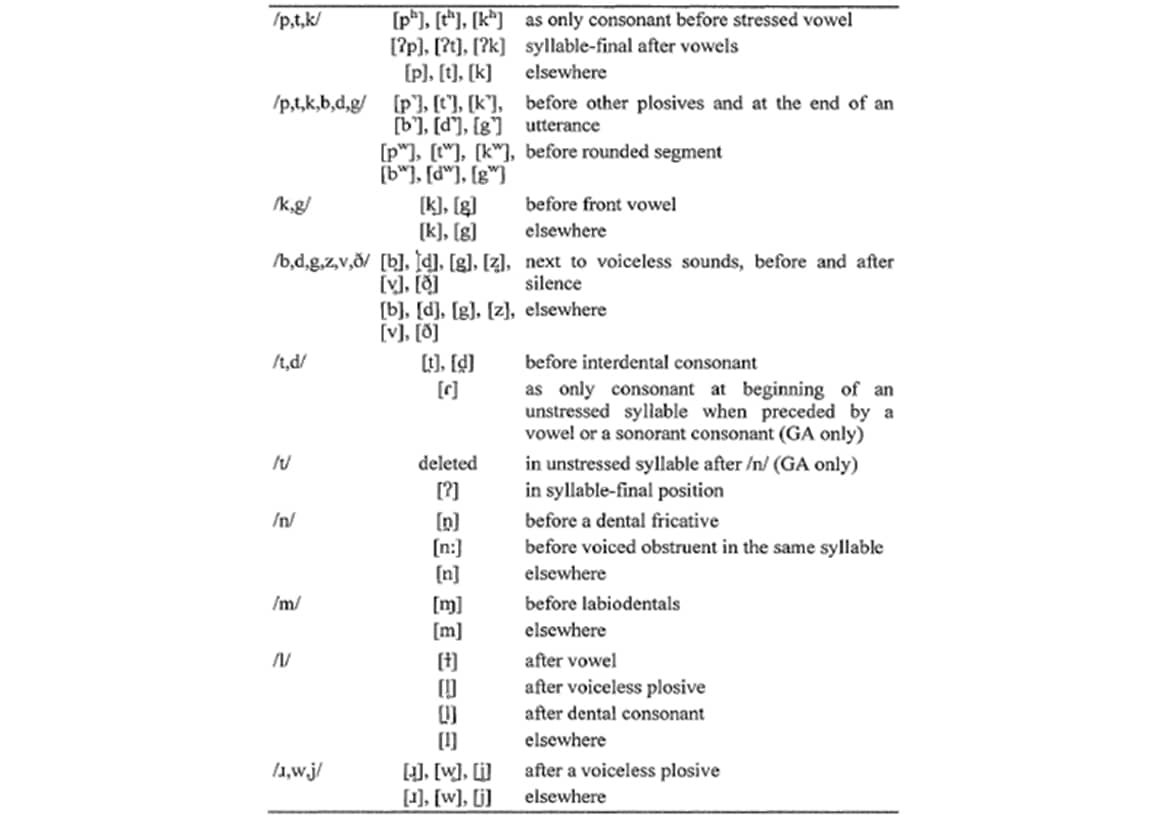

The following table shows the variation of allophones in English. Note that for each group of phonemes or phonemic units it presents the contexts in which both forms are distributed in the actual use of the language.

Allomorphy

Allomorphy is a morphological phenomenom in which the morpheme, an abstract form/meaning entity, emerges in the language being represented by at least two different morphs or allomorphs. The English -ed ending is morphologically represented by three allomorphs that are, at the same time allophones.

Allophonic variation of some consonants

Coment

It is worth mentioning that the table aims at demonstrating the linguistic variation of consonants associated to the linguistic context in which these sounds are produced. Thus, only internal factors of the language are being observed and not possible social factors that may be also related to such distribution.

Variation factors

Linguistic variation phenomena can also be observed in Phonology, for example, in phonological reduction, which is very common in any language and sometimes represented in written discourse. The following chart presents some examples of phonological reductions in English that may be possible cases of future linguistic change, especially due to their current incorporation to (informal) written language:

| ain’t ~ am/is/are /have/has + not. | She ain’t got to do anything about it. |

| gonna ~ going to | Are they gonna visit her? |

| wanna ~ want to | We wanna play soccer. |

| sorta ~ sort of | What sorta person is that? |

| lemme ~ let me | Lemme show you this. |

| gimme ~ give me | Gimme the book! |

| doncha ~ don’t you | You do have a car, doncha? |

| dunno ~ I don’t know | If they are gonna get married: dunno! |

| shoulda ~ should have | They shoulda stayed quiet. |

| lotta ~ lot of ~ lots of | We still have a lotta do. |

| gotta ~ (have) got to/a | We gotta go. |

When the sounds [t] and [d] occur as the only consonant at the beginning of an unstressed syllable and have either a vowel or a sonorant consonant preceding them, they are realized as an alveolar tap /ɾ/, a sound produced by briefly tapping the alveolar ridge with the tongue. This is an allophonic rule concerning the phonemes /t/ and /d/ that is present in American English and is referred to as flapping or tapping and observed in words such as letter and writing. In comparison to the way these words are pronounced in british English, it is observed that it is a case of linguistic variation related to geographical differences.

Respectively, these words will be pronounced:

/ˈlɛɾɚ/ ~ /ˈlɛtɚ/

/ˈraɪɾɪŋ/ ~ /ˈraɪtɪŋ/

In fact, the scientific treatment allows the identification of at least three groups of factors that are associated with three types of linguistic variations:

Diastratic variations are phenomena with no specific linguistic constraints, but of social orientation. The distribution of specific uses in subgroups of macro social groups is identified. It is possible to locate and explain, for example, differences in usage and choice of linguistic forms with same meaning in the speeches of people of different sex/gender, children and the elderly, people with different degrees of education and so on.

Diatopic variations, in turn, are those in which we find differences in linguistic usage related to regional groups that are part of a larger group. It is possible to find differences in use among speakers that are explainable due to the location in which these people live.

The grouping of diaphasic variations reflects how the use of language is sensitive to the context of communication, to the register, to the interlocutors. These factors lead us to unconsciously choose formal or informal language register. Social, historical and cultural characteristics of these groups are thus reflected in the language, which emerges as a mirror of their larger social context but that also functions as an identity factor at the individual level.

The following chart is a sample of data related to language variation controlled by social factors constrained by register:

| gonna ~ going to |

| wanna ~ want to |

| sorta ~ sort of |

If linguistic heterogeneity is controlled by specific conditioning factors, these same factors can help explain the reasons that lead a particular competing form to be implemented in the system as the only possibility of use, which implies linguistic change.

Such groupings are identified in any natural language, and variation phenomena happen at any level of language usage:

Phonological level

Pronunciation

Semantic / lexical level

Words

Morphosyntactic level

Sentences

Discursive-pragmatic level

How the speech in general is constructed

At all levels, these phenomena will be subject to pressure from both linguistic and social factors and can be observed in the spoken and written modalities.

Linguistic variation and linguistic change

It should be noted that linguistic variation does not necessarily mean ongoing linguistic change. The dynamism of the language is reflected in variation and change, but it does not mean that any variation phenomenon necessarily points to ongoing process of linguistic change. The variable pronunciation of the English -ing gerund form – [ɪŋ] ~ [ɪŋg] – exemplifies this. Although it´s been a phenomenon of variation for years in that language, it does not seem to be a case of linguistic change in progress. The possible pronunciations of the word <going> in which the final [ɡ] sound may be deleted exemplifies so:

[ˈɡoʊɪŋ], [ˈɡɔɪŋ] ~ [ˈɡoʊɪŋɡ], [ˈɡɔɪŋɡ]

Linguistic change, however, is predicted as a result of some type of variation phenomenon that precedes it. In this sense, the linguistic and extralinguistic factors involved in the variation process may show possible triggers for the implementation of change.

Linguistic diversity provides for dialectal diversity, the coexistence of variants, such as the standard language, popular and regional speech etc. The judgment of values regarding linguistic usage is independent of their linguistic nature. These are socially-oriented judgments generally associated with the role of power that the standard language plays and that is reflected in the social stratification of a given society.

Attention

The possibility that a particular linguistic form, object to social prejudice in other times, may gradually become the cultured pattern of new times is just another evidence of the lack of superiority among linguistic forms, idiolects, dialects, in short, among languages.

Orality and literacy

Sociolinguistics is a field of theoretical and practical reflections that greatly contribute to educational thinking with respect to linguistic reality and diversity for the teaching of L1 writing or of additional languages. In this sense all the issues concerning linguistic diversity turn to be mandatory for the educational ground.

Despite all the tradition regarding written language, the written modality is in no way superior to the spoken one nor there are superior oral or written ways to express ourselves. Language is expression and social representation, and in this extend it should be treated accordingly at school.

The variation depicts linguistic usage adapted to specific communicative contexts and to specific individuals. The idea that there are better languages, better cultures, more advanced peoples etc. has long been overcome although it persists in mistaken conservative thoughts, which in general do not contemplate the fact of diversity, including linguistic diversity. Just as there are no better cultures, no better dialects, no better languages, there are no better modalities and the school is in charge of providing such awareness to its students.

Educational sociolinguistics highlights the need to rethink the teaching of grammar in schools. The notion of "linguistic error" mirrors the tendency to use the standard norm as the ideal form of the language, disregarding the fact of language variation and change. Mistaken educational approaches emerge in the school context, neglecting the sociolinguistically oriented view that the language is diverse, and that each linguistic community has its own system, legitimate in itself, and in the social functions it plays for the lives of its users.

The linguistic correction at school can point to the mistaken understanding of what would be the unique and ideal way of using the language, whether in written or oral modalities. Such an attitude shows the lack of recognition of popular variants, for example, as legitimate ways of using the language. Such an attitude also reflects wrong positions and thoughts about what and how students need to learn about language.

There is a consensus that the teaching of grammar should allow the student to develop sociolinguistic skills that form him/her as a polyglot in his/her L1 or L2. The speaker of a language should be able to know how to linguistically behave in the different social spaces in which the language is predicted to be used in one way or another. Educational sociolinguistics points to the understanding of the notions of linguistic adequacy and acceptability as more appropriate to the teaching of L1s and L2s than the notion of error that is based on the parameters of traditional grammar.

The student's ability to perceive and be able to use the most conventionally envisaged forms of linguistic use in specific contexts and genres is thus developed. Such skills are objects to be considered in teaching both for the development of written and oral linguistic practices. We refer hereby to such written and oral linguistic practices as orality and literacy.

Orality and Literacy practices are seen as complementary areas of social and cultural practices:

Such practices come in various textual forms and genres and can be carried out in different registers and in a variety of communicative contexts.

Oral and written linguistic practices are on a range with multiple possibilities of textual productions that can prototypically represent the formal register of written texts or the informal register of conversation, which means that, at the end of the day, written texts may have characteristics of the oral ones and vice versa.

The existence of a range of oral and written texts and genres requires that educational practices be devoted to the teaching of such linguistic skills. For this purpose, it will be up to the school to work on the student's development in the use of language in different oral and written communicative situations in L1 and L2 classes.

Diastratic, Diatopic and Diaphasic variations, Allophones, Linguistic Variation, Linguistic Change, Linguistic Diversity... Check out the explanations with Professor Roberto de Freitas Junior:

CHECKING LEARNING

ATENÇÃO!

Para desbloquear o próximo módulo, é necessário que você responda corretamente a uma das seguintes questões:

O conteúdo ainda não acabou.

Clique aqui e retorne para saber como desbloquear.

Section 3

To describe functions and classifications of the International Phonetic Alphabet

Classification of consonants and vowels

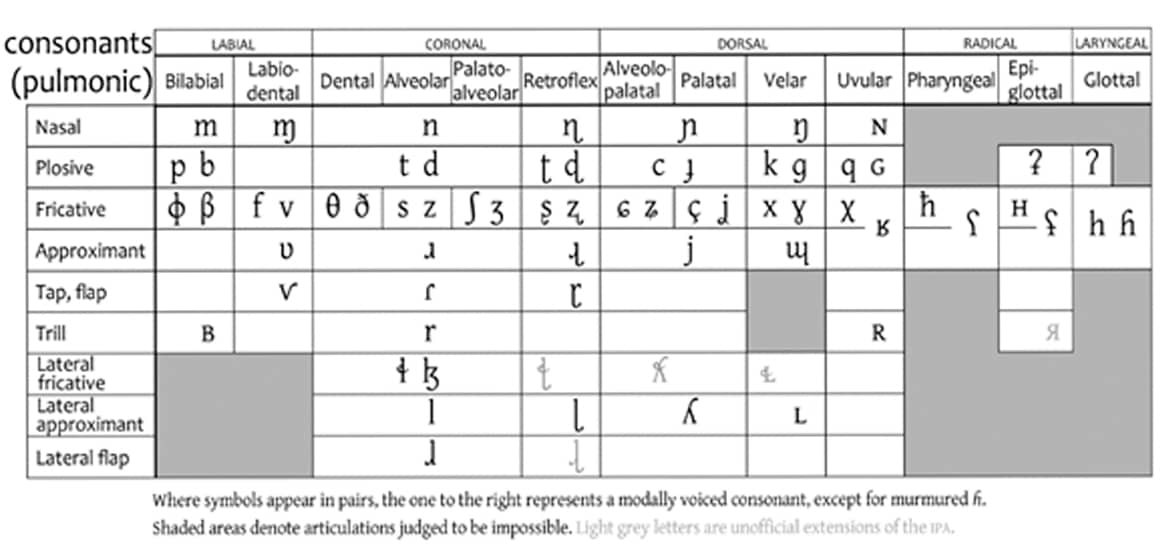

In this section, we will study the classification and transcription of English consonants and vowels, and also learn how to read the charts for the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

Speech sounds are basically divided into vowels and consonants, and, as we studied in section 1, they can be specified by the description of the:

Airstream mechanism

Vocal fold action

Position of the velum

Place of articulation

Manner of articulation

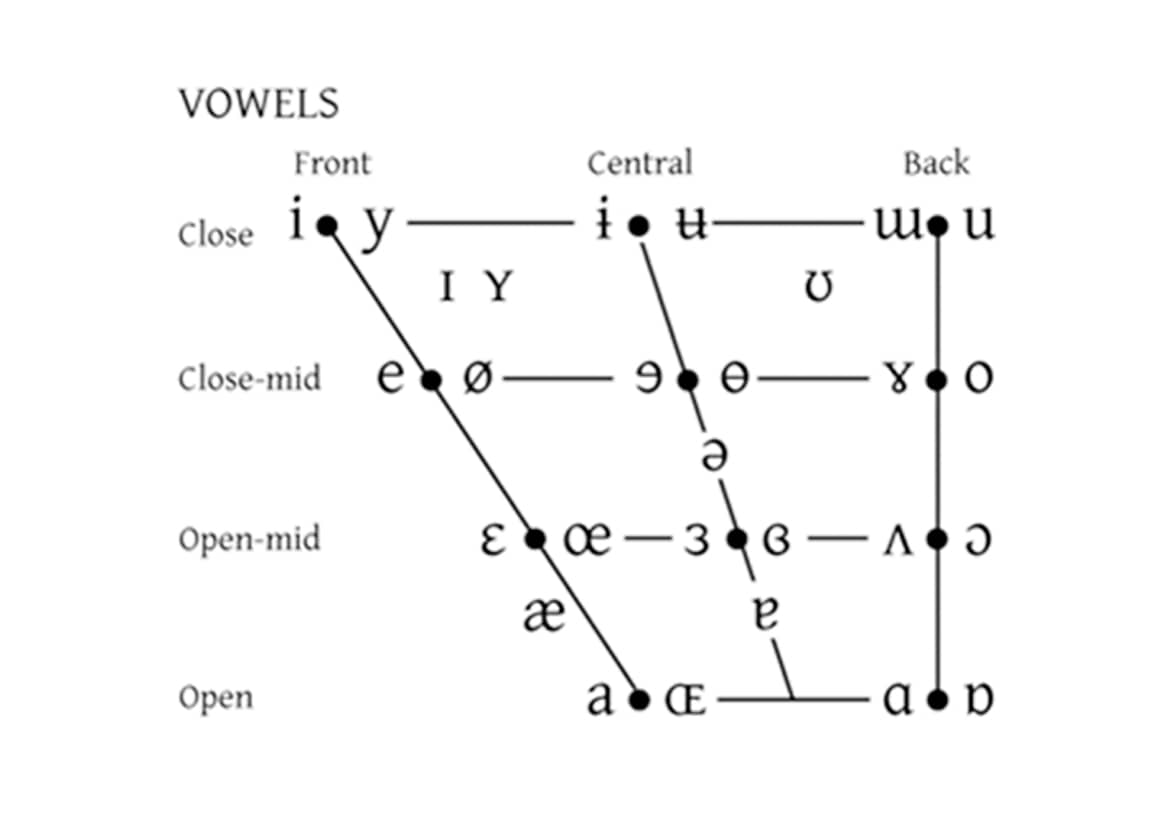

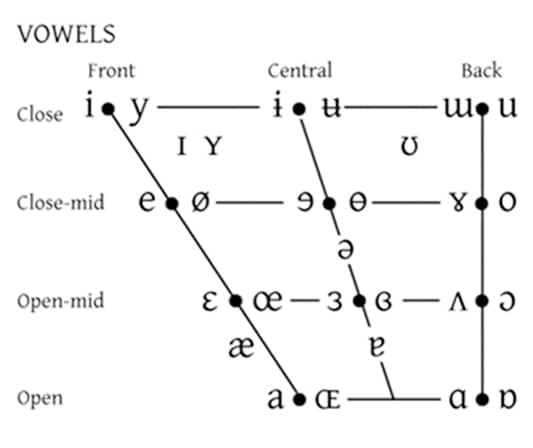

Vowels are classified according to three characteristics that also defines the description and classification of a combination of these three factors:

The following table describes types of vowels with examples and how they are produced:

Type of vowel |

Examples |

Production |

|---|---|---|

| High | [i] in bee | The tongue is close to the roof of the mouth. |

| Low | [a] in car | Considerable gap between the tongue and the roof of the mouth. |

| Mid | [e] in bed | Articulated with the tongue in mid position between high and low. |

| Front | [i] | The front of the tongue is raised towards the hard palate. |

| Back | [u] in moon | The back of the tongue is raised towards the velum. |

| Central | [3] in her | Produced with a raised centre part of the tongue. |

| Rounded / unrounded | [u] [i] |

The lips are either rounded or unrounded. |

The description and classification of a vowel is thus a combination of these three factors: vowel height, vowel location, and lip rounding. The IPA transcription symbols for vowels are the following:

It is a quadrilateral vowel chart that illustrates the shape of the oral cavity. The vertical axis represents the vertical position of the tongue and lower jaw. The horizontal axis represents the part of the tongue that is active during articulation.

Activity

This example illustrates that:

1

Vowel height is a concept related to the verticality of the tongue height.

2

Vowel location is a factor related to the horizontality of a certain section of the tongue.

3

Voicing is a factor related to the role played by the vocal folds vibration in the production of voiceless or voiced sounds.

As we also studied in the previous section, consonants are usually characterized by three other features: voicing, manner, and place of articulation. Voicing describes the Articulatory process in which the vocal folds vibrate, producing voiced or voiceless sounds. Manner of articulation is the configuration and interaction of the articulators in making a speech sound, and point of articulation is the place of contact where an obstruction occurs in the vocal tract.

Thus, the [t] sound, for example, is described as the voiceless, alveolar, plosive phoneme and the [d] sound is described as the voiced, alveolar, plosive phoneme. It is important to observe that the only difference between these two sounds – [t] and [d] – relies on the voicing trace, indicating that vocal cords vibrate in the production of the latter sound.

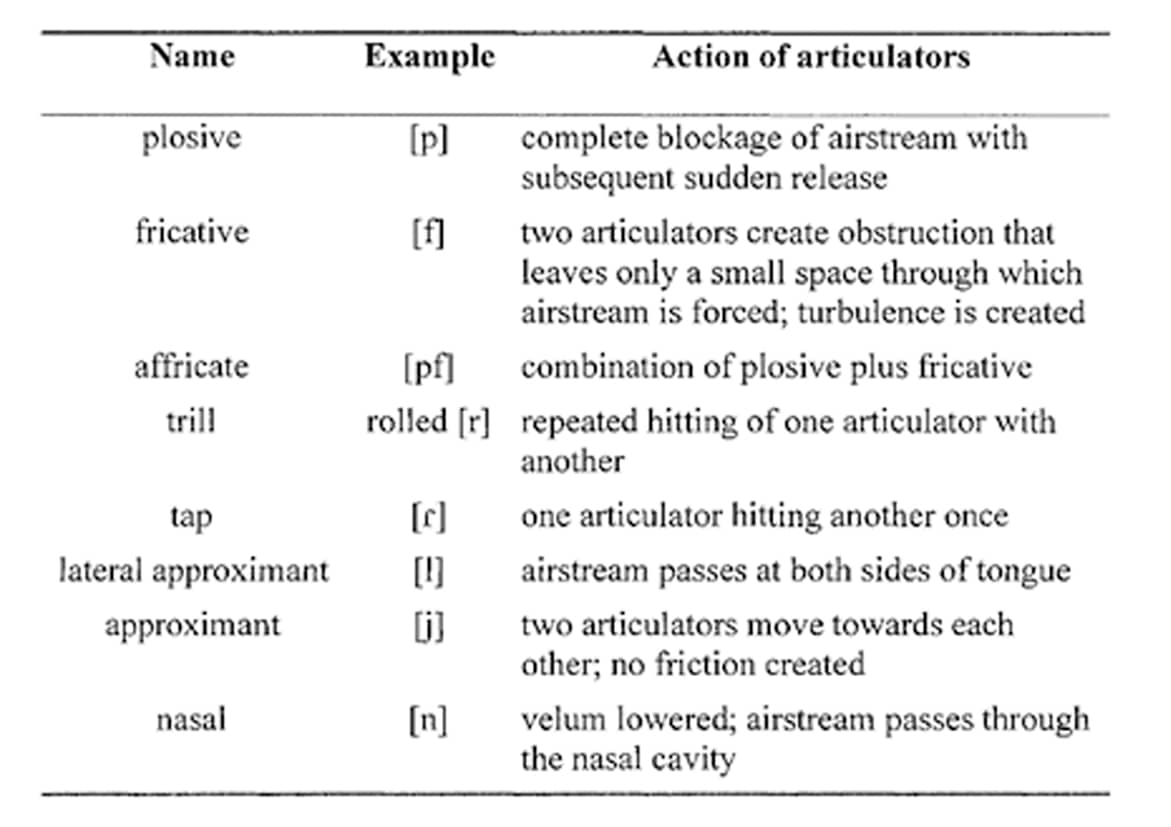

As for the manner of articulation feature, the configuration and interaction of the articulators in the production of a speech sound, a consonant may be produced by several different ways and thus will be classified accordingly. Thus, the sounds of the consonants may be:

Plosive

Fricative

Affricate

Trill

Tap

Lateral

Approximant

Nasal

The manner of articulation features together with the voicing and point of articulation ones will determine the final description of these phones. The following table describes all the different manners of articulation that underlie consonant types with examples and how they are produced:

Manners of articulation

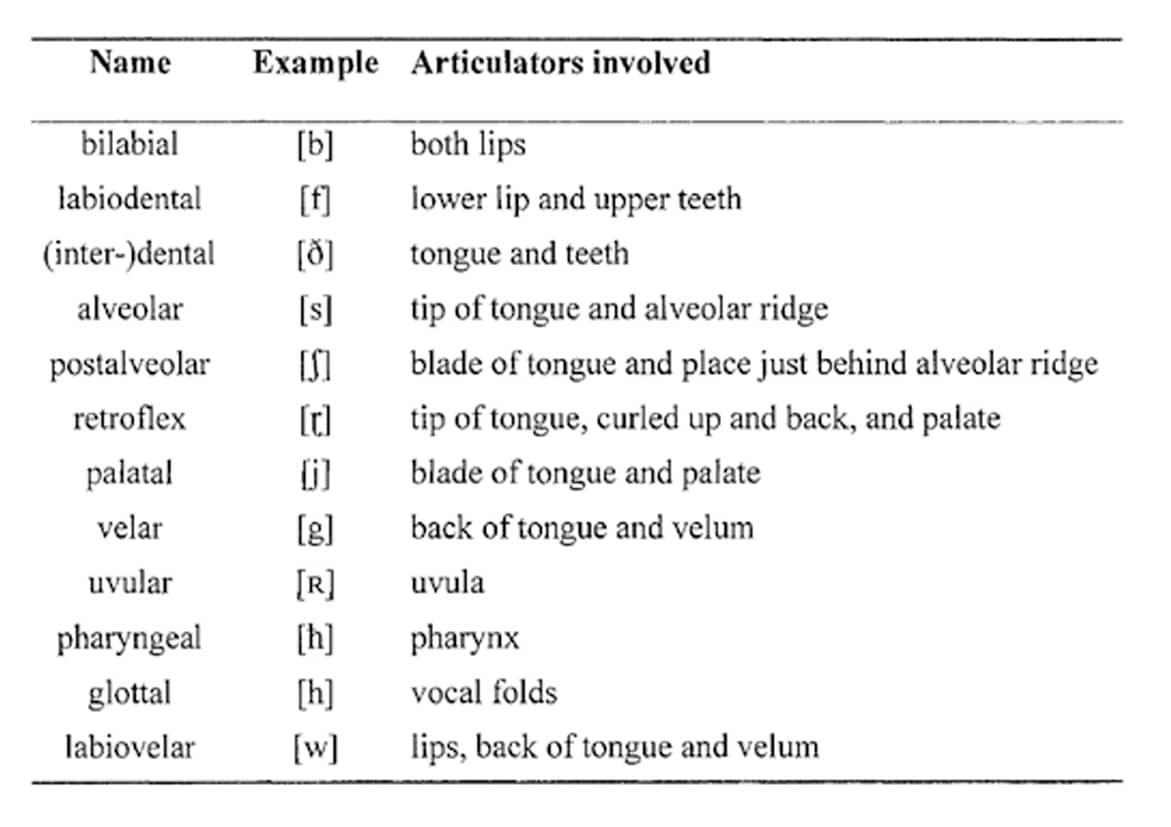

Consonants are also characterized by their point of articulation. As for the point of articulation, the place of contact where an obstruction occurs in the vocal tract, a consonant may be produced in several different places and by different articulators. Due to this classification, a consonant may be a bilabial, labiodental, interdental, alveolar, postalveolar, retroflex, palatal, velar, uvular, pharyngeal, glottal or labiovelar sounds. Once again, the point of articulation feature together with the voicing and manner of articulation ones will determine the segmental identity of these phones.

The following table describes all the different points of articulation that underlie consonant types with examples and how they are produced:

Places of articulation

International Phonetic Alphabet

International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) presents written representations of phones, i.e., transcription symbols for all distinctive speech sounds occurring in any language of the world. Phonetic transcription guarantees that a certain linguistic expression in a certain language be produced the way it is actually used in real life situations by native people of that language, which does not happen when it comes to regular writing, as we saw in section 1.

The association of written and oral modalities, as we discussed, is not perfect in any language. We do not write exactly what we say. This makes the need of a pattern that would allow the reading of words and expressions of any language possible.

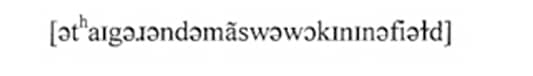

For example, the English sentence ‘A tiger and a mouse were walking in a field’ will probably be produced differently according to the speaker´s social profile and communicative constraints in which the sentence is performed. Such information which may be of extreme importance under some circumstances will not be captured by the regular written representation.

In 1886, the International Phonetic Association was founded in Paris and distributed the first phonetic alphabet. The original symbols should be as simple as possible for language learners in Western Europe and thus most of them were taken from the Roman alphabet. In the past centuries, the IPA has undergone several revisions (the last one was completed in 2005) as we seen in the following chart:

The International Phonetic Alphabet (2005)

Attention

The IPA chart can be read in the following way: each row represents a different manner of articulation and each column refers to a different place of articulation. When two symbols appear in one cell, the one on the left is the voiceless consonant and the one on the right is the voiced counterpart. Empty cells hold possible combinations of place and manner of articulation, that haven't been so far identified in any language.

Phonetic and phonemic transcription

The IPA provides possible transcriptions of sounds, words and utterances from any language in the world. If one is interested in Articulatory details of an utterance or specific sound, s/he will need to carry out a phonetic transcription. Phonetic transcriptions do not refer to speakers' mental representations but to actual realizations and are therefore carried out for real speech.

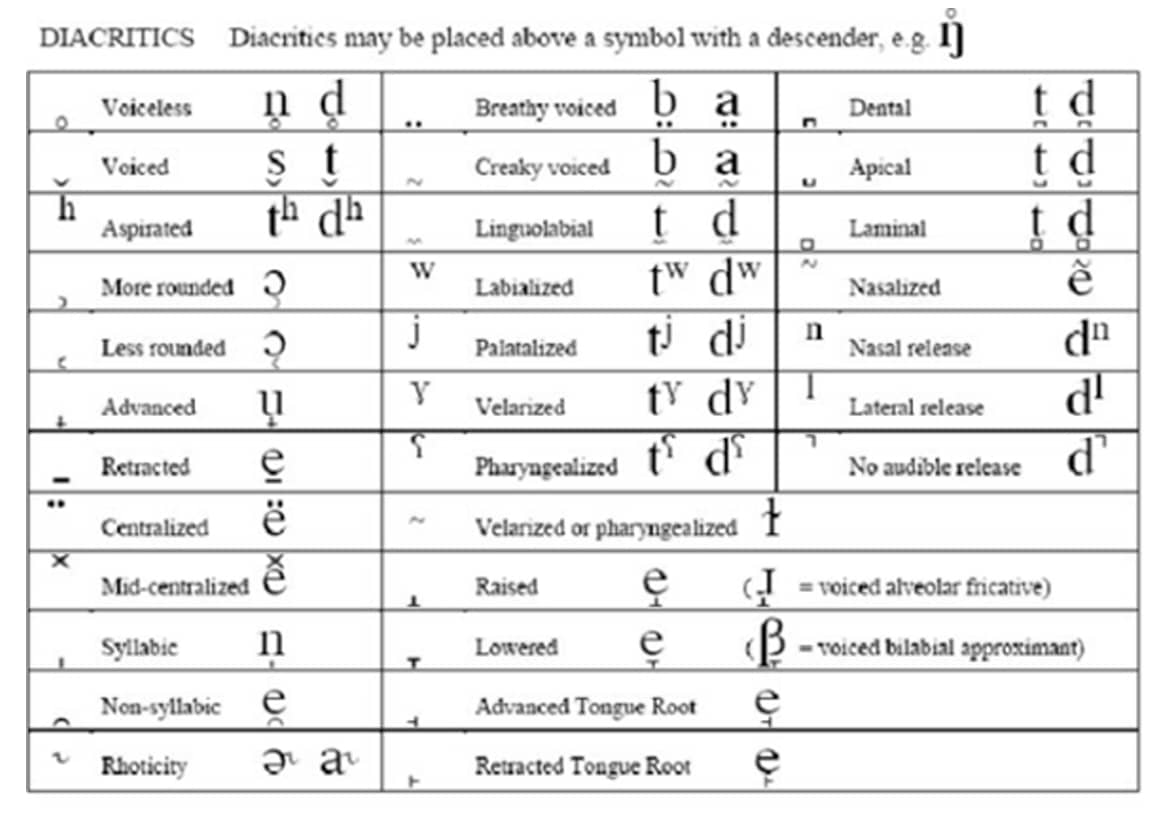

Besides the IPA symbols for the phonemes, a really descriptive phonetic transcription includes diacritics to indicate specific phonetic realizations. Diacritics are fine phonetic details and prosodic features that may arise during the emergence of a certain phoneme (like the aspiration in [ph] that is represented by the diacritic(h)).

The following chart is the IPA diacritics one. And it should be used in a fine-grained description of speech combined with the official IPA phoneme chart:

Phonemic transcriptions describe the presumed underlying representations of sounds, the speaker's cognitive knowledge about the Phonology of a language. It represents the linguistically relevant information about articulation and is the kind of transcription we find in dictionaries. Phonemic transcriptions can also be made for real speech.

There are several differences between phonetic and phonemic transcriptions. For example, in phonemic transcriptions it may be more difficult to determine word boundaries. Still only a narrow phonetic transcription of a certain word or utterance will include phonetic details such as the voicing of each segment or even allow to distinguish the exact place of articulation of sounds.

A possible phonetic and phonemic transcriptions of the utterance “A tiger and a mouse were walking in a field” are illustrated below. Note that the convention is to use:

Square brackets ([ ]) to refer to phones, the actual sounds, or to make a phonetic transcription.

Slashes (/ /) to refer to phonemes, the mental representation of the sound, or make a phonemic transcription.

Comment

A simple analysis on the differences in the transcriptions above points to the different interest of Phonetics and Phonology. For example, while in the first phonetic transcription for the sentence “A tiger and a mouse were walking in a field” the register of diacritics is observed, the same does not happen for the phonological transcription that actually aims at making sure to keep phonemic representation despite possible allophones associated to certain sounds.

Language teachers and language students may be directly benefited by being able to interpret or even produce phonetic and phonological transcriptions.

The possibility of comparing, for example, our own oral productions in a L2 to what might have been the current production to a native speaker allows the identification of problem areas in phonological acquisition. Nowadays, due to the lingua franca status of the English in our world, the importance of minimizing language transfer issues in the L2 production is definitely not the same it used to be in the past. However, it is still important for the L2 speaker to make sure to use proper pronunciation and intonation at least aiming to prevent miscommunication problems.

The management of phonetic and phonological transcription may contribute to the learning process with focus on what is actually important for successful worldwide communication. The general knowledge about the ways sounds are materialized in use and how they are cognitively represented as linguistic knowledge is particularly important for those interested in language learning.

Let’s understand a little bit more about transcription of vowels and consonants sounds:

CHECKING LEARNING

ATENÇÃO!

Para desbloquear o próximo módulo, é necessário que você responda corretamente a uma das seguintes questões:

O conteúdo ainda não acabou.

Clique aqui e retorne para saber como desbloquear.

Conclusion

Final Issues

We have presented the main points related to Phonetics and Phonology as general areas of linguistic studies. We initially discussed the concepts of phoneme and grapheme (letter), and the problems related to possible mismatches between written representation and oral productions in the written production in the first or second language (L1 and L2) that could be possible challenges for language learning. In Section 2, we discussed sociolinguistics and linguistic variation. We brought up a discussion on how these issues are important, when it comes to L1/L2 teaching/learning processes both for the teaching of oral and written modalities.

When dealing with the aspects inherent to the variation and change of languages, the sociolinguistic approach shows one of the several characteristics of natural languages, both in oral and in written form: linguistic variation. When dealing with the linguistic and social aspects involved in the process of interactional language construction, the educational sociolinguistic approach reflects the ideological and social behavior of a linguistic community, revealing important aspects about its internal management.

A great contribution of sociolinguistics is the role it plays in the construction of an educational practice suitable for language teaching. Studies focused on the language/society interface dispel prejudices about the nature and function of language, contributing with more consistent principles for its teaching.

Finally, we have presented the International Phonetic Alphabet, the IPA, showing how it represents the speech sounds of any language, allowing for a more accurate phonetic/phonological description which may contribute to the learning process of any language aiming at successful worldwide communication.

Podcast

Professor Roberto de Freitas Junior talks about linguistic variation, accents, also summarizing what we have seen so far:

Achievements

You have achieved the following objectives:

To recognize the concepts of phone, phoneme, and grapheme.

To identify principles of speech and writing quantitative variation.

To describe functions and classifications of the International Phonetic Alphabet

The chart shows that the vowel [i] is produced with the tongue in a high position and with the front of the tongue raised in the front of the mouth.